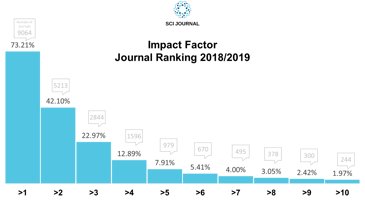

The debate over Journal Impact Factor (IF) rages on, with no end in sight. Most scientists and...

How scientists are using—and avoiding—ChatGPT

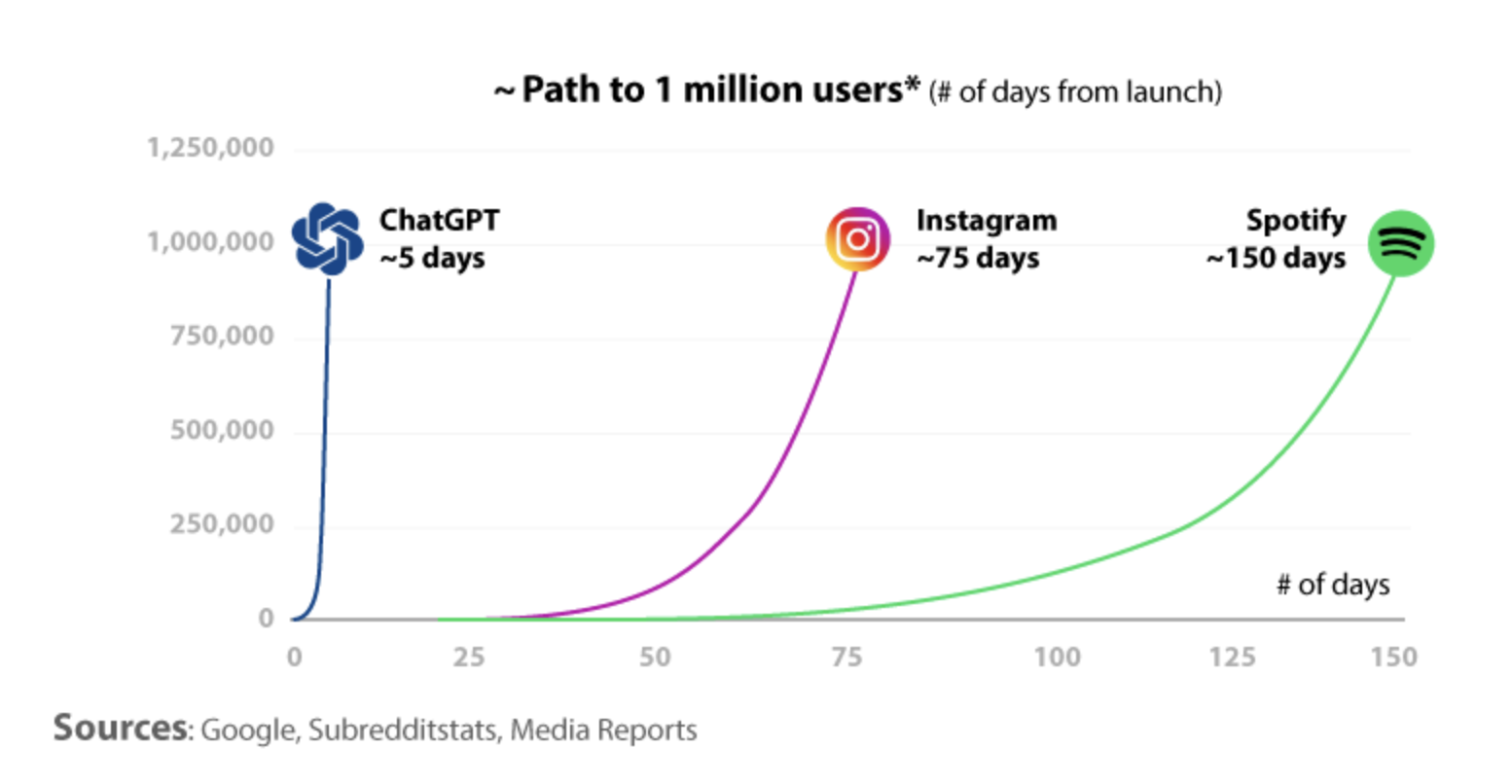

The explosive, disruptive potential of the generative AI tool ChatGPT has already changed the world of science, with a number of scientific journals moving quickly to ban the use of AI-generated text.

This includes the prestigious Science magazine, citing the following: “Authors at the Science family of journals have signed a license certifying that ‘the Work is an original’. For the Science journals, the word ‘original’ is enough to signal that text written by ChatGPT is not acceptable: It is, after all, plagiarized from ChatGPT.”

In addition, Science noted that most of their problems with manuscripts have to do with a lack of human attention and technological shortcuts leading to errors—a problem that the inaccurate ChatGPT could amplify. As Gary Marcus, emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at N.Y.U. said, “Because such systems contain literally no mechanisms for checking the truth of what they say, they can easily be automated to generate misinformation at unprecedented scale.”

On the other hand, this new tool could be even bigger than it seems, foreshadowing a new era of AI-powered scientific and technological revolutions.

At its core, ChatGPT is a text-generating model. Trained on 45 terabytes of text data, it uses a deep learning technique called “transformer networks” to generate text based on a user-defined prompt. ChatGPT is passing law exams, writing essays, acting as mental health counselors, and more—but does it have any practical use in science?

Yes, yes it does. 80% of Nature readers have used ChatGPT: for summarizing findings, for analyzing datasets, for drafting papers and proposals, for literature reviews, for writing social media posts, and more. Now that the initial hype has cooled, here are the lasting primary uses, potential uses, as well as concerns scientists have with this flawed but powerful AI.

Writing studies

AI-written studies are not acceptable for many journals. But a preprint study from Northwestern University examined ChatGPT’s ability to write scientific articles and even fool reviewers.

The researchers picked 50 real scientific articles, took the title from each, and asked ChatGPT to write an abstract based off of it. They then randomly assigned four medical professors 25 abstracts each and asked them to identify which abstracts were real and which were fake.

The results? Reviewers correctly identified the ChatGPT papers 68% of the time—meaning almost one third of the time, they were tricked. That was without a human looking over the results of the AI-generated text and making small tweaks to smooth over language or meet formatting and style requirements. Not to mention that the professors were specifically looking for fakes, so they were especially cautious.

In addition, a team of Irish researchers produced a study that convincingly demonstrated ChatGPT’s usefulness for creating scientific studies.

The team asked ChatGPT to generate a research idea, literature review, dataset, and suggestions for testing and examination. They gave ChatGPT relevant abstracts and input from academic researchers as background information. They then asked a team of reviewers to rate the output and examine if it was sufficient to be published in an academic finance journal. Reviewers generally considered the results acceptable.

The team asked ChatGPT to generate a research idea, literature review, dataset, and suggestions for testing and examination. They gave ChatGPT relevant abstracts and input from academic researchers as background information. They then asked a team of reviewers to rate the output and examine if it was sufficient to be published in an academic finance journal. Reviewers generally considered the results acceptable.

Even though ethical concerns exist around using ChatGPT to write the actual text of a study, it’s clear that there is some role for it to play in the broader scope of the writing process, whether it’s in the literature review, idea-generation, outlining, or drafting stages.

AI-assisted research

Earlier versions of GPT (the large language model powering ChatGPT) have been applied to a wide range of scientific disciplines.

In biology, scientists used GPT to identify pathogen mutations. In chemistry, scientists are using GPT to synthesize chemicals and carry out scientific experiments. In astronomy, NASA is using GPT to analyze spacecraft data. By automating analyses, taking over previously manual experimental procedures, seeking out abnormalities in data, and more, the technology is making real scientific contributions.

Looking beyond GPT reveals other ways that AI can help scientists. NewsRx’s BUTTER tool helps scientists proactively keep up with the latest discoveries in their field, monitoring over 25,000 peer-reviewed, open access, and preprint sources. Other AI technologies allow for generative modeling, which can help scientists uncover how systems work given the available data.

In the future, it may be possible to even build a “GPT for science” or a “DALL-E for science.” This sort of tech would generate evidence-backed, plain-language answers to scientific questions and hypotheses (and have the ability to make its own hypotheses).

But a number of barriers, including creating quality outputs and the fact that many scientific papers aren’t easily accessible online, have made a scientific research generative model hard to come by. Still, the present and future is bright for ChatGPT and GPT-4 assisted research.

Automating simple tasks

Setting aside the revolutionary scenario of scientific research generated by artificial intelligence, scientific researchers can bring ChatGPT into their workflow on simpler matters. ChatGPT has proved to be an effective writer and brainstormer, so scientists can take advantage of small efficiencies by delegating certain tiresome tasks to the NLG.

These include:

- Formulating emails and responses

- Drafting a researcher bio

- Summarizing topics outside of your field

- Recommending topics and studies to investigate

- Brainstorming ideas for grant applications

- Composing social media posts

- Summarizing complex topics in plain language for educational purposes

- Suggesting similar researchers or studies to explore

- Proposing approaches to a study or literature review.

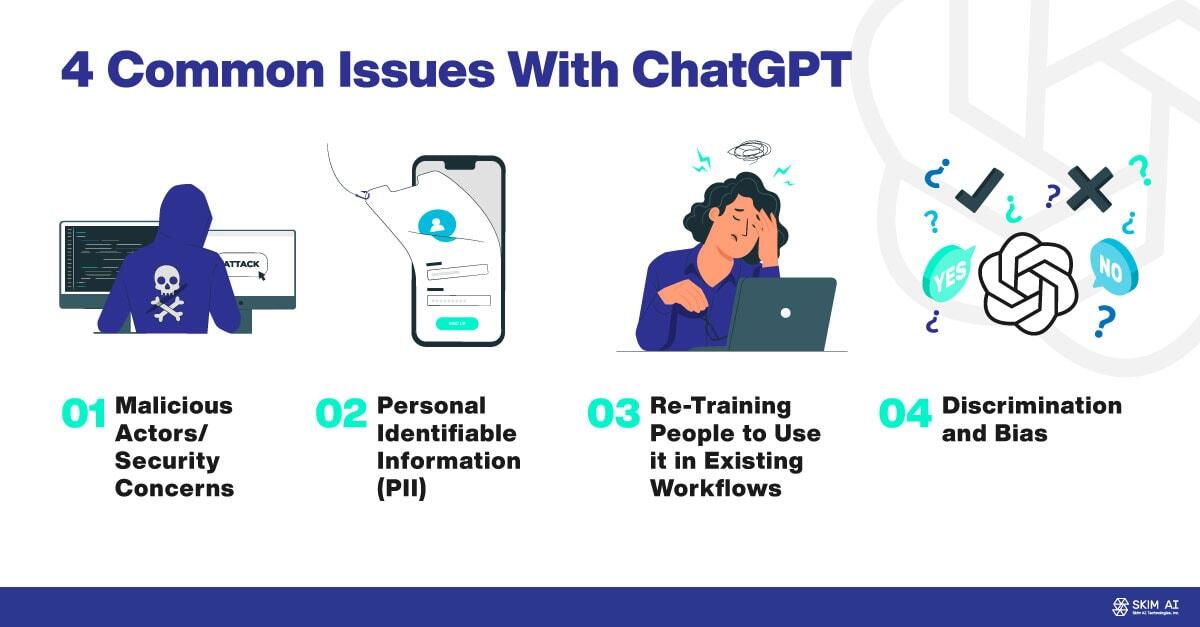

The cumulative time and energy savings can add up. However, it’s essential to keep in mind that ChatGPT can be inaccurate, and can even be seen inventing citations and sources. So users will need to check the factual accuracy of anything it generates.

Problems with bias and plagiarism

Aside from inaccuracy and unreliable sources, bias and plagiarism are two of the biggest concerns for scientists at present.

Models trained on datasets like ChatGPT will always be exposed to biases and inaccuracies present in the training data. As a result, certain biases appear in the model’s responses to queries, some of which could prove troublesome.

One simple bias is ChatGPT’s preference for long, verbose responses. A more complex, concerning one is past unequal treatment of demographic groups in the training data, which can lead to skewed results. It will be up to humans to appropriately respond to and address the biases that result from a flawed training set.

Academics also argue that the program makes plagiarism harder to detect. An academic paper published in an education journal in January described how AI tools raised challenges related to academic honesty and plagiarism—a study that was, in fact, written by ChatGPT. “We wanted to show that ChatGPT is writing at a very high level,” said Prof Debby Cotton, director of academic practice at Plymouth Marjon University, who pretended to be the paper’s lead author.

U.S. courts have already ruled that AI-generated artwork cannot be copyrighted. Whether or not they land on the same ruling when it comes to AI-generated text, ChatGPT presents a unique set of legal and ethical issues.

How to make the best use of ChatGPT

Whether or not you can make effective use of ChatGPT is determined by two main factors. 1) If your query is one that the machine can effectively address, and 2) Your prompt.

As previously mentioned, the AI can be factually inaccurate and is only up to date on events through 2021. (Although a version of the chatbot with access to current information is available with a premium option.) So it would generally be a waste of time to try to use the AI to write articles related to the news or anything that requires fact checks.

On the flip side, the AI is remarkable for its ability to remember previous statements and take into account a lot of context when responding to prompts. Using ChatGPT as a kind of virtual assistant is one of the program’s most promising uses.

By providing ChatGPT a descriptive prompt, your desired voice and response format, as well links with information you want it to reference, you are giving yourself the best chance to generate a useful response. The more detailed the prompt, the better.

Other options emerging

A number of other LLMs have started to gain traction. Not relying solely on ChatGPT could be especially useful for scientists and researchers seeking to sidestep one of the aforementioned concerns with ChatGPT—or for those just seeking an extra tool in their kit.

While many LLMs exist now, here are four useful alternatives to ChatGPT to explore:

- Google Bard: Seen as ChatGPT’s biggest rival, Bard is powered by Google’s large language model PaLM 2. While Bard is still in its infancy compared to GPT-4, Bard continually draws information from the internet, so it has access to the latest information online.

- Perplexity: Perplexity is powered using the same OpenAI API as ChatGPT (the free version runs on GPT-3). However, it is specifically designed to address the copyright problems inherent in ChatGPT by giving sources for all of its answers.

- BioMedLM: This AI model was specifically trained by Stanford to interpret biomedical language. Trained on text from PubMed, the model achieves state-of-the-art results on medical question and answer texts.

- Phi-1: Phi-1 is a language model orders of magnitude smaller than the others in this article, but for a reason. It marks a trend of creating smaller models trained on higher quality data—in this case, textbook-quality data that leads Phi-1 to specialize in Python coding.

Moving forward, scientists will likely be able to choose from smaller LLMs that are specialized to achieve certain tasks. While in the aforementioned Nature survey, a majority—57%—are using the chatbot for “creative fun,” a lot more than fun is on the near horizon. Especially as an understanding of how to make the best use of this powerful technology proliferates.

.jpg?width=50&name=DSC_0028%20(1).jpg)