←Back to resources We’ve shared two articles so far about the dire mental health crisis in science...

The Challenge of Mental Health in Science – Stress and Burnout

←Back to resources

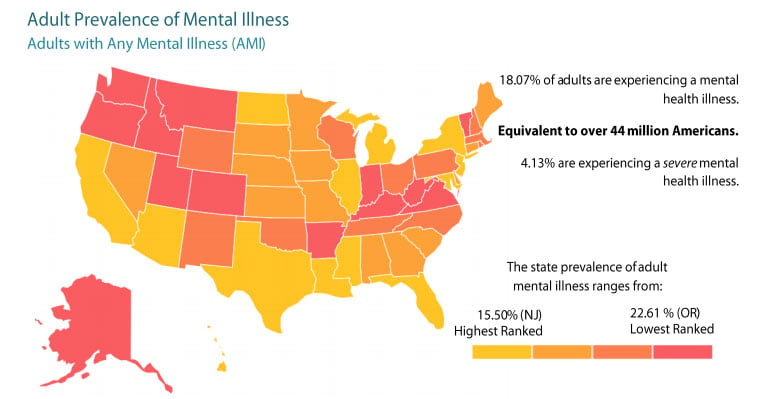

America has a mental health crisis. According to the National Council for Behavioral Health, one in four Americans have had to choose between getting mental health treatment and paying for daily necessities. And more than half have tried to “grin and bear it” instead of seeing a doctor.

This crisis extends into the world of science and scientific research. Surveys have shown that graduate students were more than six times likelier to show moderate to severe anxiety or depression on average.

The pressures of the scientific world are numerous, and can sometimes be overwhelming. These can begin before even entering a PhD program—prospective scientists are told over and over again that it’s hard to get in, that many don’t finish, that it’s difficult to get grants and nearly impossible to become a professor. Scientists face intense demands: to work long hours, to publish frequently and in high-profile journals, and to win grants, all the while being expected to bear rejection after rejection.

While the pandemic has arguably worsened the mental health crisis, both in science and around the world, greater awareness has led to more strategies for coping as well as more structural solutions.

In this series, we’ll examine the greatest mental health issues facing scientists today and how we might overcome them. In this first article, we’ll be looking at stress and burnout.

Stress and burnout

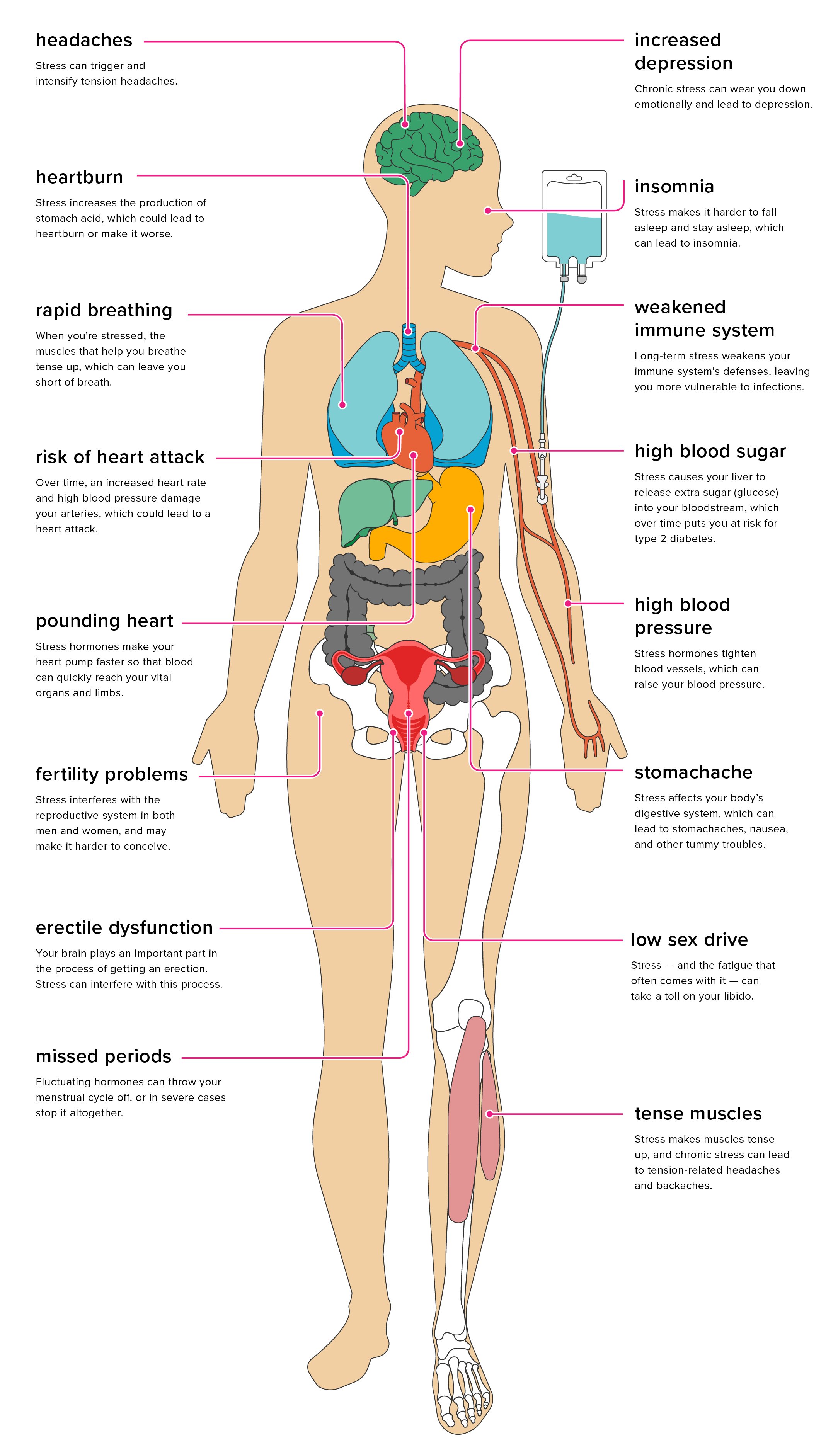

Stress and burnout are rampant in academia, where intense pressures, heavy workloads, and poor work-life balance contribute to deteriorating mental health. For graduate students, having to juggle coursework and research, while suffering anxiety over future job prospects, can be an especially swift route to experiencing burnout.

One survey found that 50% of early career researchers work more than 50 hours a week—significantly more than as specified in their contracts. And with high workload comes high stress.

These issues have only compounded with the pandemic and its logistical challenges, lay-offs, hiring freezes, and funding crunches. In a 2020 poll, the number of stressed US faculty members more than doubled compared to 2019. More than half of people surveyed said they were seriously considering changing their career or retiring early. 75% of women, burdened by childcare obligations and deteriorating work-life balance while working from home, reported feeling stressed. Other marginalized groups such as international students and LGBT+ researchers experienced a disproportionate increase in burnout. These numbers proved to be similar in Europe.

Per the Harvard Business Review, stress and burnout can also have an adverse impact on decision making. You think you don’t have time for actions that would help you in the long run, like practicing self-care or taking a vacation. You don’t utilize your unconscious mind, which can be an extremely valuable problem-solving tool when given time to wander freely during walks, exercise, or errands. You tend to withdraw from emotional support lifelines and become more rigid, defaulting to our dominant methods of problem solving rather than staying flexible and creative. All of these issues can compound for scientists, who are expected to work long hours and solve extremely challenging problems—while research suggests that our brains only have around four hours a day of intellectual work in them.

Scientists are more stressed than ever before. So how can you manage stress and burnout, especially during the pandemic?

Tips and tricks

- Read a book, go for a run, cook—anything that successfully detaches you from the source of the stress.

- Don’t be alone. Regularly talk about issues with peers, colleagues, and families. Don’t suffer from stress alone.

- Adjust expectations. Schedule more time than necessary to meet work and family obligations. Expect yourself to be tired—that way you can separate exhaustion and burnout from failure.

- Have a long-term view. Stress and burnout create both short-term and long-term problems for overall productivity and research success. It’s better to take a break now than to suffer later.

- Cover the basics. Healthy eating, adequate sleep, and periodic exercise are proven to be linked to better mental health and a stronger immune system. Ensure that your schedule allows for these bare minimum basics—and even better if it allows for some fun and socializing, too.

Stay tuned for the next edition in this series, where we’ll discuss depression and imposter syndrome.

.jpg?width=50&name=DSC_0028%20(1).jpg)

%2c%20for%20decoration%20and%20backgrounds%20with%20motifs%20of%20variety%2c%20exuberance%2c%20compatibility.jpeg?height=200&name=Floral%20celebration%20of%20spring%20Profusion%20of%20tulips%2c%20with%20raindrops%2c%20in%20full%20bloom%2c%20early%20May%20(foreground%20focus)%2c%20for%20decoration%20and%20backgrounds%20with%20motifs%20of%20variety%2c%20exuberance%2c%20compatibility.jpeg)