Scientists are severely overburdened—too many responsibilities, too many opportunities, and too...

Why studies get retracted

In the biggest research scandal of the COVID-19 pandemic, two major medical journals retracted high-profile studies.

The company providing underlying data for both of these studies—one about an antimalarial drug touted by Donald Trump, and the other about the effects of blood pressure drugs on COVID patients—declined to allow an audit of its data. Both the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet retracted the corresponding studies.

Despite this, a year later, distinguished journals continue to publish articles using the same discredited data. Retractions are an indispensable part of the scientific research process.

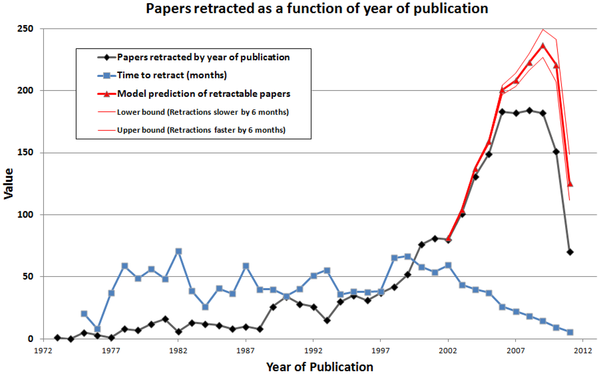

Research shows that retractions have increased substantially since 1980. In fact, by the late 2000s, the proportion of retracted papers increased ten-fold. Fraud, scientific errors, research misconduct, plagiarism, and more are among the major causes of retractions, posing continuing challenges for the world of science.

In this article, we’ll dive into the reasons behind scientific retractions, the current state of retractions, and what scientists need to know about making mistakes in their research.

Why retractions happen – human error

Oftentimes, simple human error is behind a retraction. In a study of Medline papers, honest research errors made up 40% of retractions. Common errors include the following.

- Errors in sample: A sampling error can occur when an analyst selects a sample that does not represent the entire population of data. There are various data errors that can happen with samples, but read about a few of them in our article about research pitfalls.

- Skewed statistical analysis: As discussed in our article, common error-prone areas in statistical analysis include data normality, missing data, and power calculations.

- Inaccuracies or unverifiable information: Although often simple writing mistakes, inaccurate statements or assumptions, or ones without scientific proof behind them, can be sufficient reason for editors to retract a study.

- Irreproducibility: Reproducible research is defined as a study where others can reproduce the results given the original data, code, and documentation. Replicating studies is and has long been the gold standard for rigorous scientific research. When a replication of a study produces different results, it can be a potential impetus for retraction.

- Disputes of authorship attribution: Disputes over authorship are increasing in science. Conflict among collaborators can include disputes over who should be named as an author/contributor, the order of authorship, expectations for contributors to a project, and intellectual property and confidentiality issues.

While sufficient reasons for retraction in many cases, these are examples of largely unintentional accidents. In the next section, we’ll set out the more serious type of retraction – intentional academic misconduct.

While sufficient reasons for retraction in many cases, these are examples of largely unintentional accidents. In the next section, we’ll set out the more serious type of retraction – intentional academic misconduct.

Why retractions happen – intentional academic misconduct

According to the previously cited Medline study, research misconduct made up 28% of retractions. Although the end result of retraction is the same in both cases, the following reasons for retraction are far more serious than honest error.

- Undisclosed conflicts of interest: A conflict of interest exists when an author, reviewer, or editor has financial or personal relationships that can influence their actions. For example, if a researcher receives funding from an organization that has a financial stake in a certain result of a study and does not report it. A notable example of this occurred just last year: a scientific paper claiming that smokers are 23% less likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to non-smokers was retracted after it was discovered that some of the paper’s authors had financial links to the tobacco industry.

- Plagiarism: Plagiarism is defined as taking someone else’s work or ideas and passing them off as one’s own, in this case in a research study.

- Data fabrication or manipulation: Intentionally removing data points to produce a certain result or inventing fake data is a grievous violation of scientific ethics.

- Lack of adherence to ethical protocols: Each publication has its own ethical protocols, so when it is discovered after publication that a certain paper did not meet the standards, retraction can occur. You can see an example of a publication’s ethical protocols from Wiley here.

- Salami slicing: ‘Salami slicing’ refers to using the same data set to publish multiple studies, dividing a single research effort into the smallest possible publishable units. Publishing unnecessary and repetitive information increases the amount of literature in science, but not the amount of knowledge.

- Duplicate submissions: Publishing a new paper that is essentially the same as a previous one by the same author is known as duplicate submission or redundant publication. It’s easy to imagine journals being unhappy to learn that a study they just accepted for publication had already been live in another journal. This is different from the practice of simultaneous submission, which refers to submitting the same paper to multiple publications at the same time. Simultaneous submission rules vary based on individual journal guidelines, but is frequently not permitted.

There is also a third type of retraction: when the reason is not clearly stated in the retraction notice, or is not clear to the journal editor. Editage Insights explains that this can happen when authors retract a paper without providing a reason to the publication. For example, an author who had simultaneously submitted an article, later has that article accepted by a different journal. It’s not unheard of for the author in that situation to retract it from the original publication without providing a reason. This is a sketchy move to say the least, but one possible explanation for these instances.

Trends in retractions

Studies have shown that the proportion of retractions due to fraud is in fact increasing. Duplicate publication and plagiarism have also become more prevalent reasons for retractions in the 21st century.

Daniele Fanelli, a lecturer in research methods at the London School of Economics and Political Science who has co-written several studies of retractions, says that a major factor in the overall rise in retractions is journals collectively doing more to police papers. Editorial practices at publications have improved, and journals are encouraging editors to take retractions more seriously. Another piece of “good” news is that relatively few authors are responsible for a disproportionate number of retractions, meaning misconduct is less widespread in the scientific community than the number of retractions might make it seem. The rate of increase in retractions started to slow down in the 2010s, but the number of new retractions still grows year after year.

A 2016 study by Elisabeth Bik also showed that about 2% of papers contain “problematic” scientific content that experts identified as deliberately manipulated. That’s a large portion of research, and shows the need for continued retraction vigilance.

It’s important to remember that a retraction doesn’t always mean that misconduct took place. 40% of the retraction notices on Retraction Watch came from honest errors and problems with reproducibility. Journal editors don’t want to pursue retractions because they’re also embarrassing for the journal, so editors will usually issue a correction and erratum notice first.

A simple mistake doesn’t always lead to retraction. But given the importance of scientific publishing and the continued growth of retracted papers, researchers should be vigilant to conduct their research honestly and in line with journals’ ethical protocols. With due time, there is ample reason to believe that the scientific community will continue to make progress on solving this urgent challenge.

.jpg?width=50&name=DSC_0028%20(1).jpg)