←Back to resources There are some important differences between the two Media monitoring platforms...

The Challenge of Mental Health in Science – Depression and Imposter Syndrome

←Back to resources

The mental health crisis facing scientists, academics, and all Americans seems to just get worse with each passing year. The pandemic certainly hasn’t helped. To explore mental health issues as it pertains to scientists, we’ve started a three-part article series covering stress, depression, technology, and more.

The first installment introduced the scientific world’s mental health crisis and explored stress and burnout. In this article, we’ll be exploring depression and imposter syndrome, two mental health challenges that have particular prevalence within the scientific and research community.

Depression

Depression is a serious problem among researchers. In particular, depression has been widely tracked and observed in graduate students. Researchers at Ghent University in Flanders showed that one-third of PhD students were at risk of developing common mental-health disorders, primarily depression or anxiety—a risk more than twice as high as other highly-educated groups in Flanders. The study went viral, ringing true with many PhD students around the globe.

Even worse, many students have failed to find real care at their institutions—according to one survey, just 26% of students suffering from mental health issues said they received real assistance. Experts say that most institutions simply do not have enough capacity of counselors and resources to meet demand. Universities investing more into mental health is one solution, but solving the underlying problems of overwork and immense expectations is likely to be far more effective.

How can you deal with depression as an individual in science? A lot of it revolves around self-recognition and reflection.

Tips and tricks

- Recognize your pattern—and seek help. If you find yourself struggling to get out of bed in the morning every day, recognize that a doctor might be able to help you. Many scientists who have gone through serious mental health issues acknowledge that their lives only changed for the better once they were properly diagnosed and medicated.

- Know your limits. Applying to post-docs and professorships can be a crushing, brutal experience. If it’s ruining your ability to function, it might not be worth it. See if you can stay with your current lab for another year to get back on your feet. Sometimes, an objective might be out of reach or too damaging for your current circumstances—and recognizing that is a good thing.

- Remember that you’re not alone. You can only succeed when surrounded by a healthy support network of people. If your institution, mentors, and colleagues are failing to support you or recognize you as a human being, it may be the wrong organization for you. It’s impossible for anyone to succeed when in the woods like that.

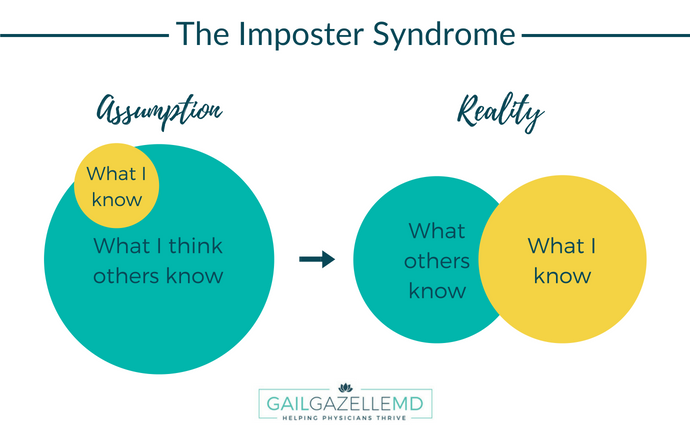

Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome is that self-doubt and sense of inadequacy that persists no matter what you’ve achieved or accomplished. While it’s a common phenomenon in many professions and industries, it has a significant impact on scientists. Science is a field that demands a series of accomplishments—high scores on exams, successful grant proposals, paper acceptances. And while failure is a normal part of the process, the feeling of being surrounded by others more successful than oneself can become a serious mental health burden.

Researchers at top institutions in particular can experience imposter syndrome after moving from environments where they were top performers to one where they are merely average. Self-doubt can be a career-killer when it ends up discouraging researchers from pursuing opportunities. “I saw many students who were shooting themselves in the foot,” Josh Drew, an evolutionary ecologist at Columbia told Nature. “They weren’t applying for grants and awards that they would be competitive for.” Many notable scientists have admitted to struggling with imposter syndrome—and have further experienced the negative impacts that this kind of paralysis can have on careers.

Tips and tricks

- Language matters. Don’t minimize your accomplishments by saying ‘just’ or ‘only’ when describing your own work, and don’t apologize for every mistake.

- Build communities. Members of underrepresented groups should seek out communities where they can see themselves represented, even if only online. Seeing examples of people like yourself having success in science can be the best kind of encouragement.

- Embrace failure. Failure is just a part of the scientific process—and the process of having a career in science. Talking about and admitting failure can create a more positive environment for all. This starts at the top, with institutional leaders and lab directors, and should extend throughout the scientific community.

In the third and final installment in the series, we’ll be examining the impact of technology on mental health—along with potential structural solutions to science’s mental health crises.

.jpg?width=50&name=DSC_0028%20(1).jpg)