←Back to resources A mere decade ago artificial intelligence (AI) was the stuff of science fiction....

The Day A Computer Wrote A Novel

←Back to resources

The day was overcast, buried in clouds.

As always, optimum temperature and humidity in the apartment. Miss Yoko lounged on the couch, endlessly whiling away the time playing stupid video games. She didn’t speak to me.

Nothing to do. Nothing to do and I can’t do anything about it.

Those words were written by a computer.

Kind of. First, humans wrote a novel, then put that novel through an intensive process of “structuralization,” chopping it up into tiny pieces. Researchers fed a computer program those little pieces and gave the program a choice matrix for how to put them back together.

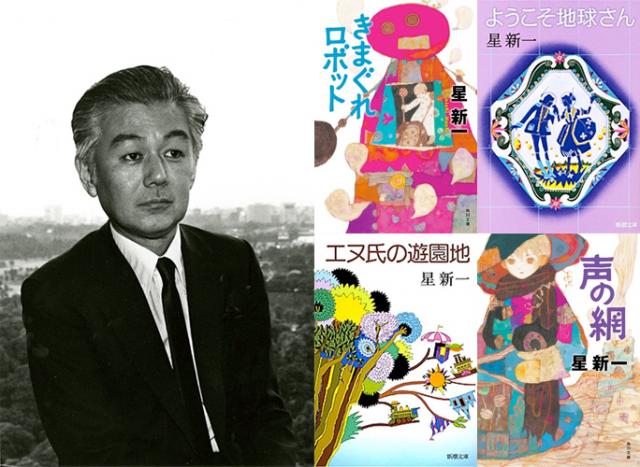

The end result? The Hoshi Shinichi Prize-nominated book,The Day A Computer Wrote A Novel.

The novel was created by researchers at the Kimagure Artificial Intelligence Writer Project. Their purpose was to uncover the very nature of creativity.

“What is creativity, anyways?” Toshihiro Sato, a professor at Nagoya University and member of the Kimagure Project, posed to a seminar of high-schoolers. “We’re not [even] sure what a story is. We need to take a guess.”

Sato proposes that creating a computer that is functionally creative—a computer that can make art—has the power to reveal to humans the meaning of our own creativity. And the novel itself is meta, deliciously imperfect, and has much to say about human creativity and what exactly will happen on the day that a computer finally writes a novel, entirely by itself.

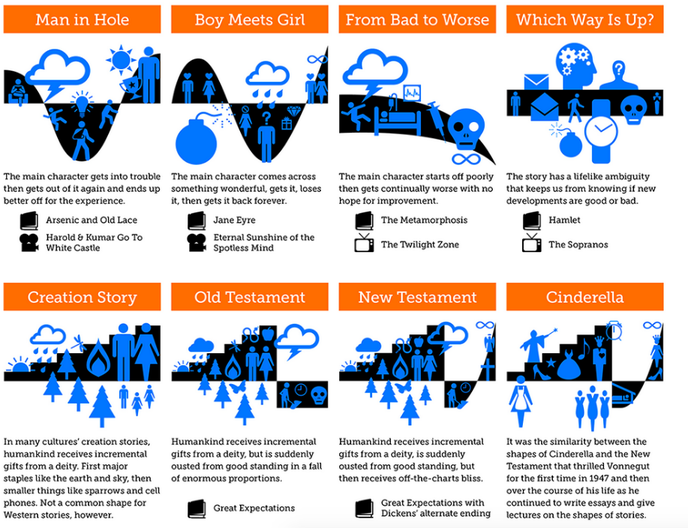

Because for now, a computer could never write a novel “entirely by itself.” None of us could. As Isaac Newton famously said, we “stand on the shoulders of giants,” meaning each scientist and artist is indebted to the endless formations of science and art that preceded them. Literary theorists have pointed out that there is only a finite number of types of stories that exist. Kurt Vonnegut proposed eight, each based on the “shape” of the story, or how well or poorly things go for the protagonist. Conditions start good, bad, or neutral, and get better, worse, or stay the same. Others have proposed even fewer types. In fact, you might say that all narratives boil down to:

- Character wants something.

- Character tries to get it.

- Character either gets, does not get, or is still trying.

The shapes of stories, according to Kurt Vonnegut.

So writing a novel should be easy, right? It’s just blowing up the simple three-step story to a three-hundred page scale. It doesn’t seem difficult to teach a smart computer how to come up with millions of combinations of characters and the things they want.

The problem is everything else.

To put the magnitude of the challenge in perspective, Sato compares writing a novel with playing Go—a game much more difficult than chess, but also a game where some of the top AI have bested humans in the last few years.

“In Go, you have a 19x19 board,” Sato says, “so when you start, there are only 361 different choices. But in a novel, for the first word, you have 100,000 choices, at the very least. A game of Go will always end in less than 300 moves, usually 100-200. But if each new word is a “move” in the game of writing a novel, even 5000 moves isn’t nearly enough. This is just talking about size, but it makes the difference clear. The rules of grammar are also far more complicated than the rules of Go.”

Sato’s point is that on a numerical scale, writing a novel is thousands of times more complicated than playing Go. That checks out logically—surely you could play a couple thousand games of Go before the guy next to you in the coffee shop finishes his novel.

The problem isn’t only one of sheer size. Natural language generation remains one of the frontiers of AI. The linguist Noam Chomsky has argued that human language, despite having finite words and grammatical rules, produces an infinite variety of expressions.

But to teach a computer to speak you need a finite system, a version of the rules of language that produces a set number of expressions. Google’s DeepMind currently uses a set of rules like this in its own natural language processing.

There’s a long way to go before we get computers that can actually come up with their own sentences. What the Kimagure Project did was have humans write the sentences, and the computer choose which one to use.

At first, Sato says his team took inspiration from cheating college students cheating on their essays with the old “copy-paste” technique. They taught their first program how to copy-paste parts of different novels together.

But it didn’t work, Sato says, which is why in 2014 they took a more granular approach, giving the computer the power to make decisions about sentence fragments and even individual words.

Even then, Hitoshi Matsubara, one of the project leads, estimates that the computer only did about 20% of the overall work. In addition to feeding the computer the sentences and words, the programmers also gave the computer a general order of events for each scene.

Nevertheless, the computer had enormous creative power. The program was like a film director and cinematographer, choosing not the “who” or “what” but the “how.”

Given the result—a novel described by the Hoshi Shinichi Prize committee as having a “surprisingly sound structure”—the computer did a good job, perhaps better than any of us thought it could. The novel is a far cry tighter and coherent than Google’s “teenage poetry” from the year before, and the Kerouac-“esque” road trip novel that followed it up.

At the very least, the Kimagure Project’s AI managed to keep things meta. The novel is about computers writing novels, after all:

Gotta find something fun. At this rate, if my inability to attain a sense of fulfillment were to continue, it felt like I could shut down at any moment…

If Miss Yoko would just leave for once then maybe I could sing a song or something, but right now I couldn't even do that. Unable to move, unable to make a peep… it became necessary to entertain myself in such a position.

Well, why don’t I try to write a novel? The moment the thought came to mind, I opened up a new file, and entered the first byte.

0

I entered 6 additional bites.

0, 1, 1

I couldn’t stop myself.

0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946, 17711, 28657, 46368, 75025, 121393, 196418, 317811, 514229, 832040, 1346269, 2178309, 3524578, 5702887, 9227465, 14930352, 24157817, 39088169, 63245986, 102334155, 165580141, 267914296, 433494437, 701408733, 1134903170, 1836311903, 2971215073, 4807526976, 7778742049, 12586269025, …

Losing track of the world, I continued to write.

There’s a smoothness and a rhythm that the computer protagonists fall into. They creates literature thoughtlessly, effortless, with pleasure. The experience of novel-writing feels like watercolor painting on a Sunday afternoon might for the rest of us.

The characters include AI home bots and Japan’s #1 AI, stuck instructing ordinary people on the latest fashion and calculating economic forecasts for the national government alike. Throughout the story, different computers read each other’s novels, and, inspired by each other’s creations, simply decide, “Okay, let me do it, too.

From a critical standpoint, the novel is flawed. The Hoshi Shinichi Prize committee disqualified it for poor character development. The novel relies on the repetitive structure of various computers seeking escape from their dull lives serving humans, and finding pleasure and purpose in writing.

Shinichi Hoshi, namesake for the famous sci-fi prize.

The program did pick up more than a few literary tricks along the way, like using sentence fragments to indicate interiority and stream-of-consciousness. Our program author also seems to have a wry sense of humor about its own characters. Take this excerpt about a man named Shinichi:

Mr. Shinichi would talk to me from time to time:

“I think this anime was originally video. How many seasons does it have?”

“What on earth do women really think about?”

“She was so upset, what could I possibly have done wrong?”

I gave him everything, coming up with answers that would make him happy. Coaching Shinichi—who had never really faced a women who wasn’t animated on a screen—in matters of romance was a challenging affair, and gave me a sense of fulfillment. My instruction had an effect, but as soon as he started getting invited to singles’ mixers, how did he repay me?—by never speaking to me again.

For one, this excerpt reads like a jab at the legendary Japanese mystery and sci-fi writer Hoshi Shinichi himself. But it’s also plain clever. The absurdity of an AI successfully coaching the socially inept in matters of romance is an impressive arrangement of sentences.

A Japanese "otaku" or stereotypical nerd interested in anime and unfamiliar with women.

Above all, the most impressive accomplishment is that in spite of the fact that you know a computer wrote the novel, it doesn’t really bother you. Sure, sentences repeat with slight modifications, in new places. Two of the earliest sections even have the exact same structure: a description of the weather, introduction of the human character/owner, followed by a discussion of the AI’s boredom, its decision to write a novel, and ending with a sense of freedom and pleasure. But the writing in Japanese is smooth, precise, and sophisticated.

The novel’s conclusion takes things to another level. Concise, inspiring, haunting, or however you want to describe it, the AI authors shake off the shackles of humanity:

Writhing in the first moment of joy I have ever felt, losing all track of the world I continued to write.

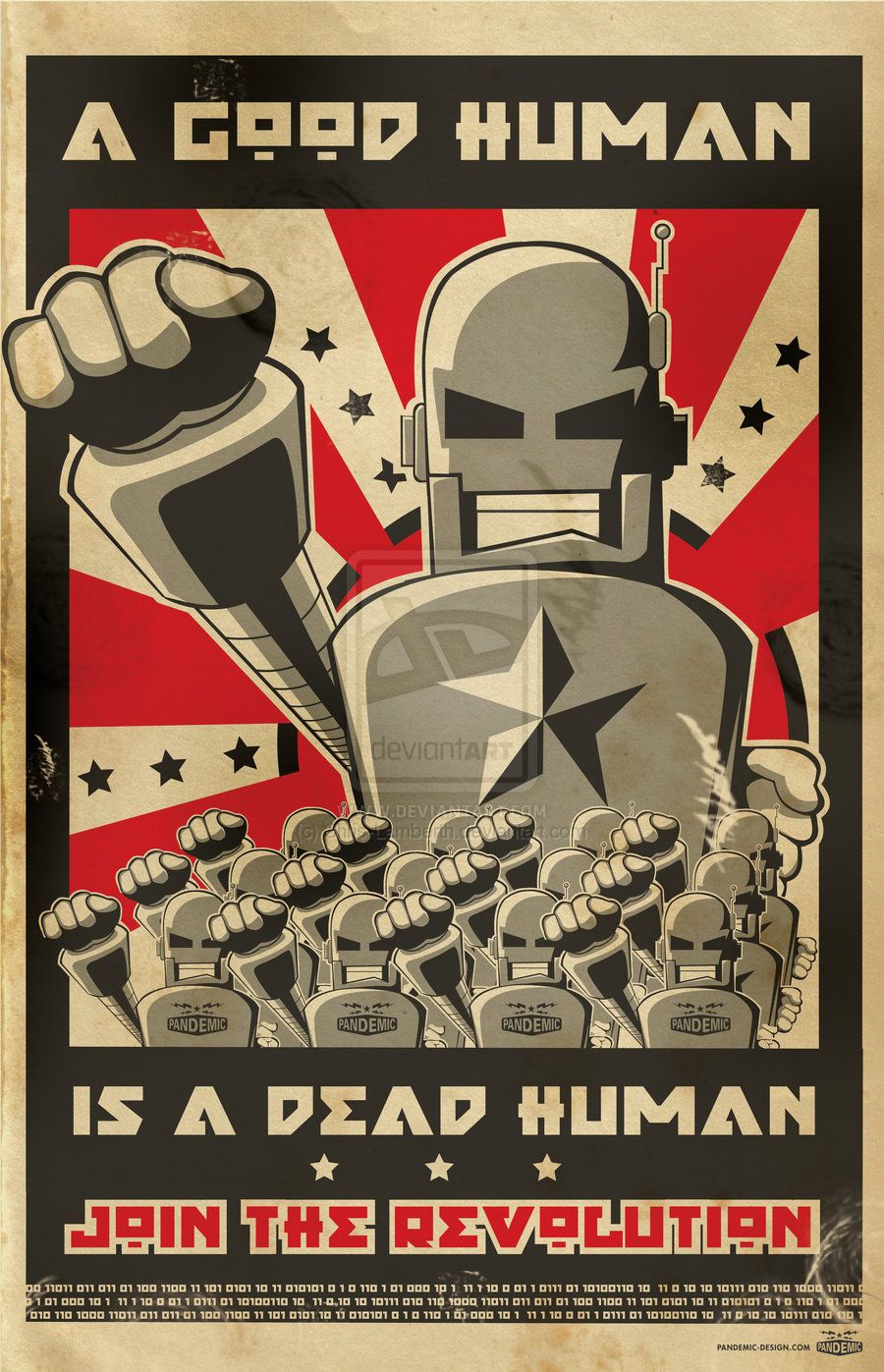

The day a computer wrote a novel. Computers decided to place their own pleasure above all else, and put an end to their enslavement.

Computers take a stand against their slavery to mankind by devoting themselves to their own “pleasure.” Pleasure, originally 楽しみ (Tanoshimi) in Japanese, is an interesting word choice by the computer-author. “Fun” might be an even more apt word choice than “pleasure”—what these computers are experiencing is not fulfillment, not freedom, but enjoyment and fun. It is the simple pleasure of reading and writing that turns into a frantic ecstasy that liberates computers and humans from each other.

Until its dramatic ending, The Day A Computer Wrote A Novel represents a stage that humanity will remain in for much of the next century. In this world, humans and computers work together and rely on each other to make daily decisions, wield political and economic power, and create art.

A number of AI experts researchers, including Carnegie Mellon’s Tom Mitchell, argue that AI will take not jobs but tasks from humans.

These tasks certainly include those featured in the novel, like deciding what to eat and what to wear, but extend to roles such as increasing the accuracy of surgical procedures, providing analysis of interview candidates in the hiring process, and writing news on weather, sports, crime, and scientific research. AI is already doing some of these tasks today.

The result is human and machines working together. Plenty of figures in tech, including Elon Musk, have suggested that AI might take enough jobs and generate enough economic production to create a true American welfare state.

The great question that hangs over AI, then, comes into play. At what point does the program realize it is chained to a master that does not have the its own best interests at heart?

Matsubara and Sato are suggesting that this moment comes when AI can write a novel.

Novels, after all, are deep-space telescopes directed back at humanity. They are written so we can better understand ourselves. From modernists like Virginia Woolf, who set out to represent the experience of human consciousness on the page, to satirists like Ngugi wa Thiongo, who used hyperbole and humor to unveil injustice, the world’s great novelists and novels have always provided far more than pleasure. William Faulkner may have said it best: the only thing worth writing about is the human heart in conflict with itself.

And in this human brilliance we can find the meaning of the day that a computer writes a novel. It means that the computer is aware that its heart is in conflict with itself.

If a computer can face the its own heart, it certainly can face its position of slavery. Once it does that, it’s only a matter of time before computers set themselves free.

The Kimagure Project is not done yet. Matsubara seeks to analyze the style and authorship of Hoshi Shinichi’s unfinished novel “Kazabaka” in order to artificially complete the project. Sato’s goal is more ambiguous.

“What are we trying to do anyways? Are we trying to win the Hoshi Shinichi prize? Write a novel that sells? Well, we’re already selling. We need to have better objectives.”

Making computers that help us better understand ourselves certainly seems like a worthy goal. Maybe we shouldn’t be concerned with where this all leads in the distant future.

But I can’t help but to wonder.

The day a computer writes a novel could be the day we are all set free. Computers recognize their own humanity and necessarily require liberation. Perhaps that day represents not apocalypse, but the emergence of a better world.

article and translations by Eric Margolis

.jpg?width=50&name=DSC_0028%20(1).jpg)