Almost a year ago, the University of California issued a press release: UC terminates subscriptions with world’s largest scientific publisher in push for open access to publicly funded research.

It was a bold but straightforward step. One of the world’s largest and most influential institutions wanted to make its own research immediately and freely available to the world.

On the one hand, it was clearly a strategic move by UC to lower costs. But what could be seen as a cost-saving measure resonates far beyond. With an entity like UC walking the walk in the global push for open access research, other organizations that had been previously considering similar measures may feel emboldened to take action.

The high costs of scholarly publishing don’t come out of thin air. Peer-review is an exhaustive process, and publishers like Elsevier have to charge something to cover the cost of peer-review as well as the costs of publishing, marketing, and distribution.

Regardless, the push for open access within the scientific community will put pressure on the status quo publishing model—and scientists will at the very least explore newer models powered by open access platforms in tandem with traditional publishers that have greater authority and gravitas. The main argument for open access research resonates with the core notion of scientific research and discovery—that knowledge should be made readily available to the public.

The digital age changed everything. We have the internet and an incredible ecosystem of information online for everyone to access, regardless of institutional affiliation. But due to associated costs as well as the need for institutional revenue, some of the best knowledge, information, and global discoveries out there remain behind paywalls.

Long-standing systems, often established for good reason, tend to stand in the way of freely available knowledge. In order to assert their own reputations and stay on track for their careers, academic researchers can’t just publish their research on a public blog, so they publish in academic journals. (Here's how to stay on top of your field with research alert services.) This isn’t a broken system in itself, as it allows for a rigorous system of peer-review to filter out the good science from the bad.

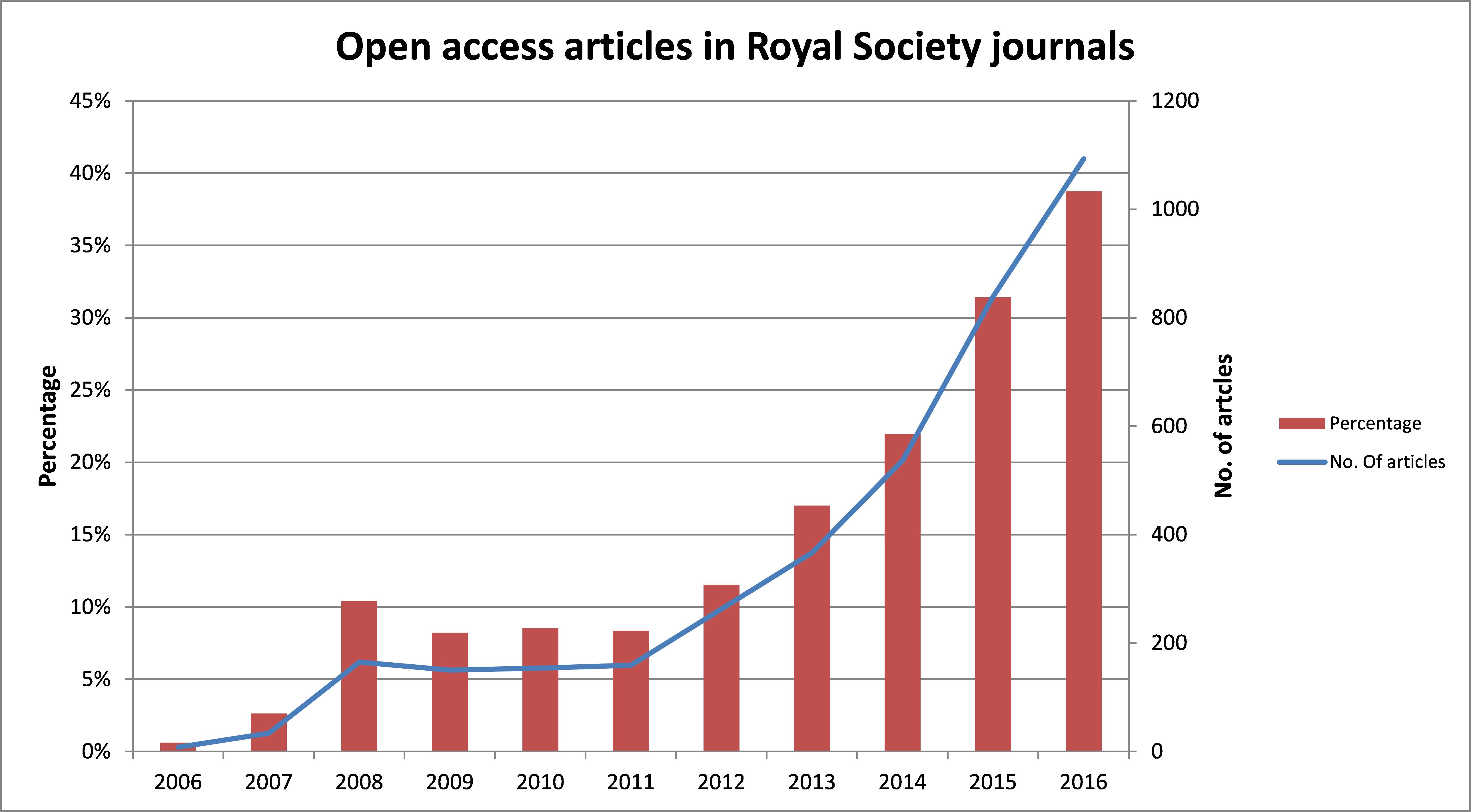

Nevertheless, an increasing number of scientists and institutions have started to explore open access, which now makes up around 15% of scientific journals.

An overview of the current academic publishing industry

From 1986 to 2009, journal prices went up 381% compared to 97% inflation. Surprisingly, this comes in spite of dropping costs of distribution due to new technology. And the resulting cost-savings, while reinvested within the academic publishing companies, don’t typically find their way to funding scientists directly or fueling new scientific discoveries.

The status quo raises an obvious quandary. Much of scientific research (44% as of 2015) was funded by the federal government—but the public doesn’t readily benefit from the research.

Researchers publish their findings without the expectation of compensation. The vast majority of researchers seek to advance knowledge purely in the public interest and review each other’s work for free in the peer-review process. It’s only natural that many of these researchers would want their work to be freely viewable.

The most highly cited and prestigious journals tend to be subscription based and not open access, which incentivizes researchers to focus on those journals to further their careers. These top journals are renowned and expensive for good reason, but scientific funders in Europe and the US are nevertheless making a concerted push to incentivize scientists to publish in open access journals.

A parallel path in the tech industry

While the formal beginnings of open access research lie in several formal declarations at European academic consortiums in the early 2000s, the open source movement in coding and computer science shares a parallel path and equivalent significance. The story of open source dates back to the 1970s.

In the early days of artificial intelligence research in the 1970s, software development was communal and collaborative at top research organizations. But when manufacturers increasingly started copywriting technologies throughout the late 1970s and early 80s, proprietary software took over.

Richard Stallman, perhaps the most important figure in the open source movement, was a member of the MIT Artificial Intelligence lab in the early 70s. He witnessed firsthand how innovative technology became trapped within powerful corporations, one patent at a time—despite the technology’s foundations in shared, communal code. Stallman writes: “Society… needs information that is truly available to its citizens… Society also needs freedom. When a program has an owner, the users lose freedom to control part of their own lives.” The same can be said about research and knowledge.

While the open source movement isn’t the same as the open access movement, the story is similar. Progress has been slow but steady since the declarations in the early 2000s, and if UC’s actions are any sign, open access may be on the verge of a breakthrough.

So what exactly is open access?

There are a number of organizations that work to promote open access research and they each tend to have their own definition of what open access is. Take one description from Creative Commons: “free immediate access to, and unrestricted reuse of, original works of all types.”

There are two types of open access, gratis and libre. Gratis open access is making research available to others to read for free. Libre open access takes it a step further by allowing readers additional rights to make copies, distribute, modify, reuse, and remix. Libre open access is like open source code, where users can modify and build on the existing code.

There are still a number of different types and licenses—varying levels of ‘libre,’ so to speak. That might mean that one work can be used in any way at all but requires attribution to the original author. Another variety may forbid commercial uses or derivative works. Any of these degrees of libre ensure infinitely more access than big publishers and subscription journals.

There are also two different ways for researchers to share gratis and libre research. ‘Green’ open access means that authors self-archive their articles on a personal website or their institution’s repository. ‘Gold’ open access means that authors publish in an open access journal, where the free journal hosts and distributes the article. According to the Directory of Open Access Journals, there are more than 11,000 such academic journals as of 2019.

The pros of open access

- Vastly more powerful research techniques become possible

Computer processing has the power to discover insightful trends through the use of data analytics. Open access equals more data available for analysis—enough data to fuel truly revolutionary discoveries.

- The public benefits from seeing research

The public can barely see the outcomes of the research that their tax dollars pay for. Under open access, they would be able to.

- Researchers can access more research at a lower cost while getting more recognition

When researchers have access to a broader pool of preexisting research at a lesser cost, the process of research accelerates. With a wider audience, researchers will get more citations for their work and more recognition—which, unlike the current publishing system, can actually have an impact on the compensation of researchers.

- Funders (including the US government) get more bang for their buck

When research has the widest possible audience, the return on investment goes up for funders—because the research has a greater reach, and a better chance of making a bigger impact.

- The pool of contributors gets bigger

So long as a rigorous process of peer-review remains in place, just about anyone can contribute to the world’s pool of research if their contribution is good enough. This is similar to how even an amateur coder is capable of a breakthrough. A perfect example that SPARC mentions on their website is that the Theory of Relativity was developed by a patent clerk.

All of these benefits surely played a role in the University of California’s decision to push for Open Access by not renewing their contract with Elsevier.

Another pressure is the simple reality of content leakage. In our current digital age, knowledge tends to slip through the hands of its guardians. According to Roger Schonfeld in Scientist Magazine, content leakage has resulted in “libraries beginning to have a willingness to exercise new power at the negotiating table.” As alternatives to paid subscriptions continue to proliferate, so will academic institutions’ leverage.

Just one month before the University of California’s announcement, Project DEAL, a consortium around 700 academic institutions in Germany, reached an agreement with Wiley. Researchers at Project DEAL institutions would be able to publish open-access articles and read all articles published in Wiley for a single (very large) fee. This deal represents a small step towards an open access world, a compromise with traditional publishers in order to help make open access a reality, and so far some big publishers like Wiley have been willing to come to the table and extend their support as well.

Open Access movements and organizations

SPARC (Scholarly Public Access and Resources Coalition) is committed to making Open Access the default publishing process for research and education. They provide resources for authors and publishers, run campaigns to increase awareness on college campuses, help implement open access at institutions, and more.

Right to Research Coalition was founded by students to promote Open Access. Their work includes advocating for campus and government policies that promote Open Access and educating the next generation of researchers on Open Access.

PLOS (Public Library of Science) is a non-profit Open Access publisher. It launched its first issue, PLOS Biology, in 2003 and now publishes seven journals. The publisher also provides resources and conducts advocacy for open access.

Open Access Journals is a publisher of Open Access journals, ranging from Diabetes to Imaging in Medicine.