The Knowledge Age is an era in which artificial intelligence processes information for humans and turns it into knowledge, and in some cases, decisions.

In the endless sea of digital information that defines the 21st century, AI can sort through the noise and deliver knowledge to us with the precision of GPS coordinates. The Knowledge Age will prove an era that transforms who we are and how we live--and it is an era well on its way.

We live in an era where we can look up anything we want to know, and speak to friends and strangers from around the world. Advertisements for products that we do and do not want pop up on our browsers. Notifications bombard our phones—text messages, emails, news, stocks, spam, the scores of sports games.

This is the world of the Information Age, with its host of advantages and disadvantages. But what’s next—what’s on the horizon at this very moment—is poised to give humans more powerful tools than ever before, transforming our technology and our lives.

The Knowledge Age: an era in which artificial intelligence empowers, enhances, and facilitates human knowledge. Human knowledge becomes swift, direct, muscular—we will have access to answers rather than questions, conclusions rather than data, truths rather than trends.

This era simultaneously threatens human agency and creativity while building a road towards an advanced and equitable society. Yet above all, the most important thing to understand about the Knowledge Age is that it’s already on the horizon.

The Information Age

To discover how we eventually get to the Knowledge Age, we first have to reflect back on the Information Age. And in order to trace the origins of the Information Age we have to go all the way back to the 1970s, when the Internet was developed by the U.S. Department of Defense for military purposes. Over the next two decades institutions began to use the Internet for data storage and private communications.

The appearance of the World Wide Web in the 1990s allowed companies to sell products online. Airline tickets, hotel reservations, books, cars, homes, and more became accessible in a few clicks. Universities began publishing their research data on the Internet. Corporations began organizing their work online. The development of email allowed for near instant communication between individuals.

Since then, information online has exploded. Maurice De Kunder calculated in Scientometrics that there were 4.66 billion web pages online in March 2016. According to Cisco’s Visual Networking Index Initiatives, global internet traffic annually reached 1.1 zettabytes in 2016. A zettabyte is 1 sextillion bytes (1021 bytes). That’s a thousand million million million bytes. That’s how many grains of sand there are on Earth.

Characteristics of the Information Age

Information Over Products

We can define the Information Age as the shift from an economy and culture based on the production and consumption of manufactured goods to an economy and culture based on consumption of digital and computerized information.

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 2010, the value added by finance, insurance, real estate, and information was double that of manufacturing. But before the 1980s and 1990s, businesses produced manufactured goods, and people received information as products, as manufactured packages. Newspapers, magazines, news networks, and radio networks were relatively condensed, and packaged as physical entities either on a page or in a box. There were only a few, centralized television programs providing information.

While we used to consume information as products, today we consume products as information on the web. Instead of being fed packaged information, much of the information existing in the world lies before us. Consider eBay, where you can sell a product to anyone on the internet, and total strangers from all over bid on your product. While your product is still a product in itself, the internet turns it into a piece of information—the existence of an available product—instantly findable, knowable, and buyable by anyone at all. Thus in the Information Age our unit of consumption has shifted from products to information.

An Age of Google

The Age of Google is an age where you can type whatever you want to learn about into a search box, and with either a little or a lot of digging, find that information.

The key factor at play here is that Google usually holds what you’re looking for--whether or not it’s easy to find. Sometimes it is easy, and sometimes it’s hard. But it’s there (probably). Most of the time Google will also throw information at you that you don’t want—company advertisements, or search results that erroneously show up. But you nonetheless make yourself privy to vast amounts of information--including what you want to know--with a couple of clicks.

An Age of Analysis

Individuals, corporations, and institutions have changed the way they make decisions. Whereas decision-making in the past was heavily based on a mix of expertise, intuition, and human computation, we now rely on computer computation. Computers can take millions of pieces of data and analyze them, so it makes sense that efficiency-seeking corporations, organizations, and individuals would turn to computerized analysis. Businesses can develop databases of customer information and history and use that to optimize outreach and marketing strategies. Institutions can develop tax policy by computing the outcomes of past laws.

While this age of analysis by and large increases efficiency by taking human time and human error out of calculations, there are drawbacks as well.

Impacts of the Information Age

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

Convenience. It’s easy to find simple answers to everyday problems. Directions, food, entertainment… no matter what it is, “There’s an app for that”. |

Distractions. With so many sources of information, we lose our capacity and willingness to focus on a single task. It’s easy to get lost in the noise. |

|

Big data. Big data crunching can allow firms as well as individuals to make decisions that maximize profit and efficiency. |

Too-big data. "Paralysis through analysis”—people get scared to make decisions without ‘crunching’ the data. As a result, some firms choose to do nothing at all rather than act without data, even at times when no amount of data would yield an adequate solution. |

|

Consumption. Consumers can easily compare hundreds of different products in an instant. |

Overconsumption. Consumption becomes almost too easy. An information age society needs to somehow stay attuned to the connection between people and people, and people and nature. |

|

Virtual resources. The shift of resources and databases to online reduces clutter and increases accessibility. |

Inequality. The haves and have-notes of society become defined by Internet access. One must be technologically literate to be successful. |

|

More content. We have access to seemingly limitless data and news. |

Less can be more, too. But we need to spend significant time sorting through what’s important. We're no longer defined by our local networks and communities. |

The Bridge: Artificial Intelligence

The technology that takes us from the Information Age to the Knowledge Age is artificial intelligence. Rapid development and implementation of AI in the past 5 years signals AI technology’s coming dominance, and provides clues on how the Knowledge Age will unfold.

AI does not mean intelligent humanoid robots. As Google tells us (or rather, as Google’s AI tell us), it is merely “computer systems able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, and translation between languages”. In the near future, applied AI in particular will become commonplace. Applied AI refer to AI programs applied to solve human problems in daily life as well as in government and all industries—just as computers today are applied for use in all areas of human life.

So how does AI lead to the Knowledge Age?

If computers are able to make human-esque decisions, we can use computers to complete some of the more tiresome tasks that humans usually complete—like sorting through too many Google search results. By relegating time-intensive tasks to AI, the “information” that humans receive when we interact with technology will be fundamentally different. AI will parse through it, match it with our preferences, and even condense or summarize it. As a result, the “information” we access will no longer be information. Rather than see 100 search results, we'll receive the answer to a online search query. Rather than use a calendar app to schedule appointments, we will have our schedules taken care of for us. Rather than sort through data that might suggest sound tax policy, we will directly see the optimal approach.

Not data, not numbers, not facts. It will be knowledge—computers will give us conclusions, decisions, ideas. The fundamental units of our consumption will again shift, before from products to information, this time from information to knowledge. Hence, the Knowledge Age.

Knowledge Age Technologies

Let’s look at a few different technologies that point towards the emergence of the Knowledge Age.

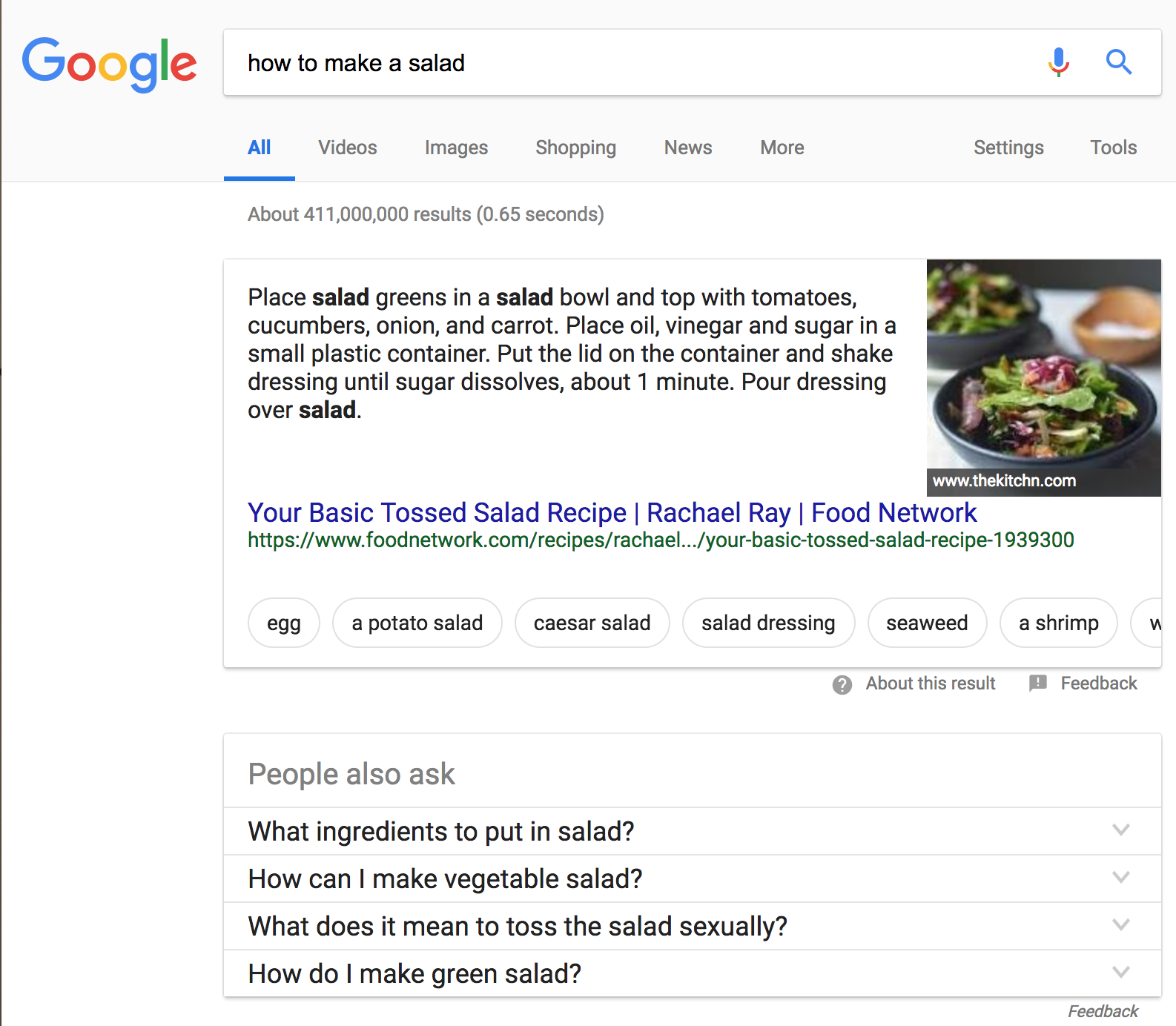

Google's Answer Box

Google’s Answer box demonstrates the fundamental shift from the Information Age to the Knowledge Age. Let’s say you want to know how to make a salad. On Google, let’s say 5 or 10 years ago, you would google “how to make a salad” and have to sort through the results, finding the best option by trial and error. Nowadays, you google “how to make a salad” and the answer pops right up in that Answer Box.

This is a shift from information (a bunch of links to salad recipes) to knowledge (the actual salad recipe). Now, this “knowledge” is simple knowledge. But it’s knowledge nonetheless. The Answer Box delivers the user an accurate answer, allowing the user to skip deciphering an entire article to find it.

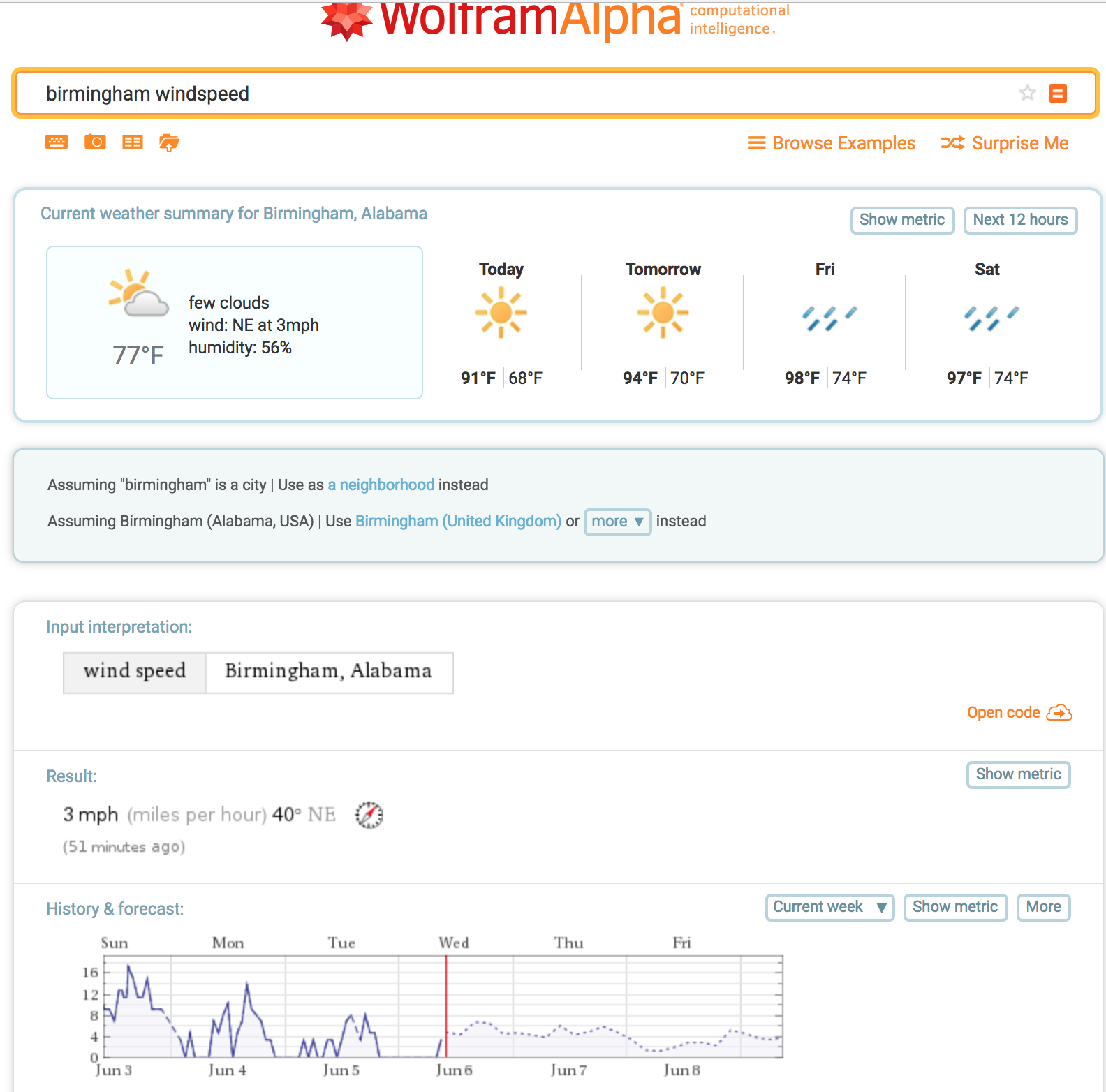

Wolfram Alpha

Wolfram Alpha is a website that provides knowledge rather than information. It relies on massive databases, some of which are generic and available online, some of which are specialized databases not accessible on the internet by the general public. Like Google, Wolfram Alpha uses natural language processing to interpret what you type. A search for “Birmingham windspeed” results in a graph displaying the average speed of wind in Birmingham, followed up by additional related data. Wolfram Alpha provides first and foremost the answer to your question, and then additional information tailored to your query.

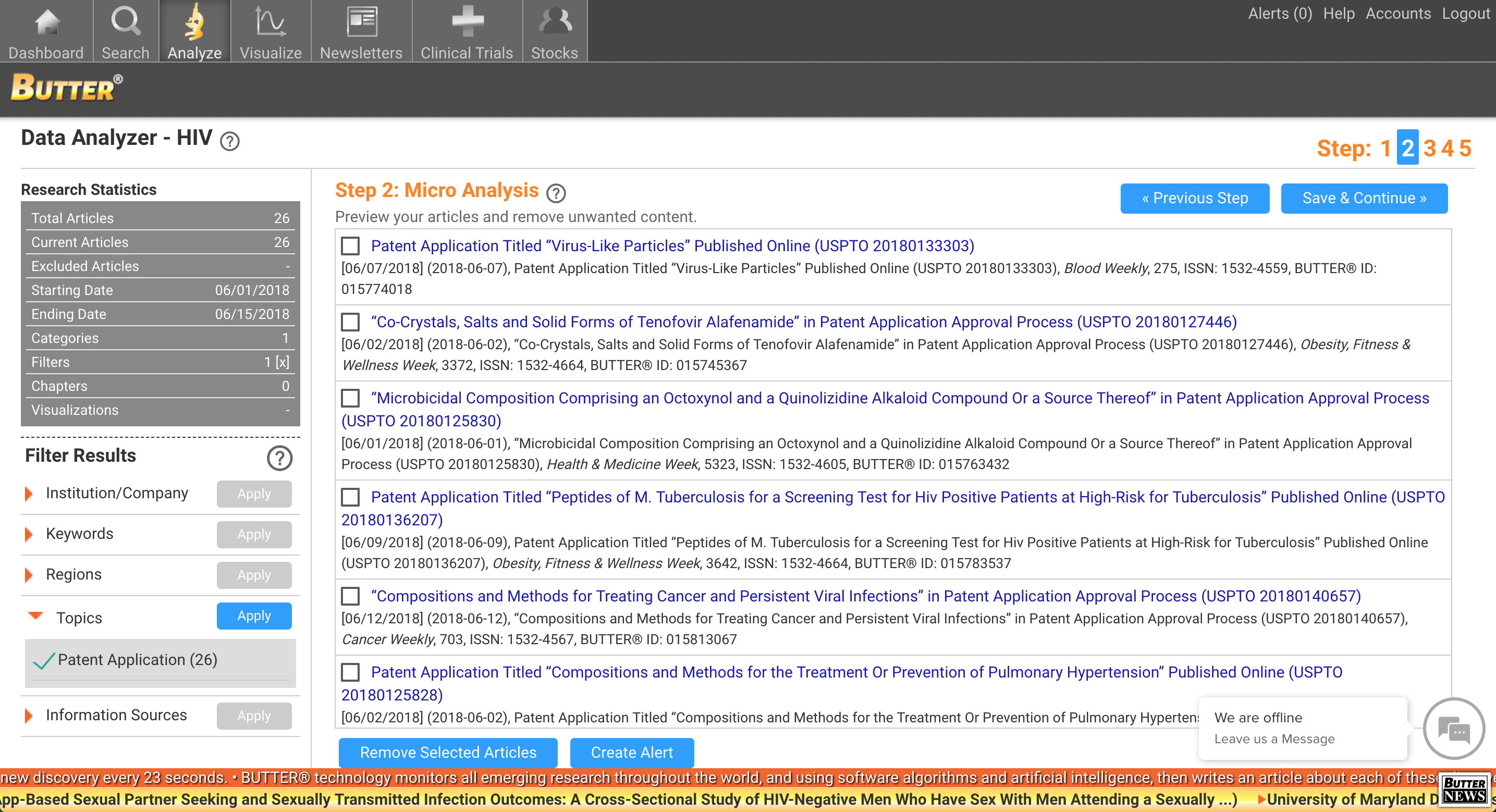

Butter

Butter is used by corporations and scientists to find solutions to their research, rather than the comparatively simpler questions that Google Answer Box or Wolfram Alpha answers. Butter can find knowledge about more complicated subjects, such as the latest solutions in the world of steroids and supplements, or the implications of patents on a new technology. Butter searches the world of peer-reviewed content, but does so in a way that converts information into knowledge.

- Butter does quality control, weeding out articles with inaccurate information and incomplete data.

- A user completes their search for keywords.

- A user is presented with analysis of their search—where the results are coming from in the world, what type of results they are (research, patents, or other formats), and what companies and institutions the results are coming from. A user can then narrow the field of results based on seeing what content they don’t want.

- Data is presented as news briefs and reports, written by computational journalism and AI that determine the source’s premise, process, and conclusion. From there, Butter can link out to the original study.

- Butter can format and export a whole dataset of research briefs as a PDF report, giving a user a set of knowledge tailored specifically answer his or her question.

Through this series of steps, Butter converts what used to be information (a field of search results) into knowledge (concise research briefs about scholarly studies done in response to a user’s query), analyzed and processed by AI.

Alexa and the Amazon Echo

Alexa is built to transform daily life around AI. Rather than web browsers and mobile screens, intelligent, conversational bots just might be the means by which we access the world wide web in the not-too-distant future.

By conversing with Alexa, the Echo can play our music, set our alarms, keep track of to-do-lists, and provide weather, traffic, and other real time information. It can control smart home appliances like heating, lighting, and washers, dryers, and ovens. By skipping the human processing component of an activity like ordering a toaster on Amazon, Alexa allows to get directly to a result—or knowledge—without an intermediary stage.

Alexa and similar technologies allow us to run our daily lives on AI that generates knowledge and solutions from the database of the internet—information that we will no longer directly see.

The Algorithmic Newsfeed

While years ago Facebook had a chronological newsfeed, displaying posts from friends in the order that they appeared, Facebook’s newsfeed now has a complicated algorithm to show you, in true Knowledge Age spirit, what you care about. (Of course, many of us complain about our Facebook newsfeeds, but this represents the transitional moment that we are in—the algorithms are constantly improving.)

Again, the fundamental shift here lies in artificial intelligence deciding to show us information we care about, so we don’t sort through an overwhelming amount of information on our own. The algorithm attempts to choose the best content out of thousands of potential stories, and places them first in your newsfeed, based on:

-

Who posted it (the more you’ve interacted with the author in the past, the more likely you are to see the post)

-

How others engaged with the post (if lots of people are engaging youwill be more likely to see it)

-

What type of post (is it a status, link, photo, video, event? If you engage more with a certain type of post, you are more likely to see that type)

-

When the content was posted

Twitter and Instagram have similarly updated their newsfeed technologies to follow similar algorithms. In the Knowledge Age, the information we see is tailored to what algorithms think we want to see.

Characteristics of the Knowledge Age

Knowledge Over Information

The fundamental process that we will observe in the Knowledge Age is that AI takes data, or information that humans used to sort through on their own, and come up with some sort of result. That result represents the “knowledge” that we no longer have to find on our own.

Beyond the technologies described in the previous section, this tendency will manifest in a lot of human-AI collaboration. For example, AI goggles worn by a surgeon or chef might provide analysis about information AI is good at understanding, like the exact temperature of a dish, or how many millimeters are between two ligaments.

An Age of Artificial Intelligence

AI will begin to touch all fields and become a prominent part of our daily lives. AI research assistants could become the norm for business professionals. While some jobs will be lost to AI, new opportunities will also open up. The integration of AI into our “smart homes” will provide new convenience for 21st century living.

Applying AI to work on more practical human problems has enticing benefits and worrisome drawbacks. For example, AI may be excellent at generating sound policy solutions efficiently, regardless of whether our politicians can pass them. However, AI tends to work opaquely, and the methodology used by a machine learning program to generate an outcome may not be able to be easily understood by humans--and so any inherent flaws are even harder to decipher.

An Age of Creativity

The use of applied AI for tiresome fact-checking, data-mining and entry, and data analysis opens up the opportunity for humans in their jobs to innovate. If AI allows newspapers to cover basic news like weather, crime reports, and sports results, then journalists can create more dynamic, exciting stories, independent from or aided by AI. In all fields AI will begin to take care of our most boring, repetitive tasks, giving us crucial time for creativity and innovation.

Impacts of the Knowledge Age

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

Lifestyle. We no longer need to worry about simple everyday problems, such as our commutes or our morning coffee. |

Less autonomy. Human autonomy is at risk—with the aid of AI, will we begin to stop asking questions as computers provide us easy answers? |

|

Economics. An automated economy, or an economy based on human-AI collaboration, is more efficient and productive. Surplus wealth can be spent on education, healthcare, and even basic income. |

Changing job market. White and blue collar workers stand risk of displacement into new fields or unemployment. |

|

Consumption, again. Consumer decisions become easier, automatically selecting the most cost effective and even ethical products. |

Overconsumption—again. Consumption becomes even easier than it currently is—which many would argue is already too easy. |

|

Powerful computer insights. AI will be able to parse sets of data impossible to decode in the past, allowing AI and researches to develop solutions to increasingly complex problems. |

Fewer human insights. Loss of control over the entire research process could possibly lead to a increased apathy towards discovering new knowledge and an over-reliance on computers. |

|

Opportunity. A safer and more comfortable society--and a world of possibilities. |

Uncertainty. An undetermined world of challenges and questions. |

Why It Matters

In our future, in the Knowledge Age, AI will process information and even some decision-making for us in our work lives, home lives, and eventually in nearly every facet of society.

On the one hand, the Knowledge Age is the future of science fiction. It allows humans to live more easily, safely, and smartly than ever before while simultaneously threatening the meaning of human existence by threatening to take away human autonomy and decision-making.

On the other hand, the Knowledge Age has already begun as a logical progression from the Information Age. Computers are starting to be able to provide us with intelligent, sorted knowledge instead of overflowing information. Salient, relevant, and intelligent decisions come to us through our smartphones and computer apps rather than endless lists of data and arrays of notifications.

Where exactly will all this knowledge lead us?

It remains hard to say, and that is precisely why understanding the Knowledge Age matters. Understanding the transition that we are facing at this very moment empowers us to make strategic decisions about how to implement AI—perhaps so that we can reap all of the benefits, without losing the spark of human spirit that has brought us this far.