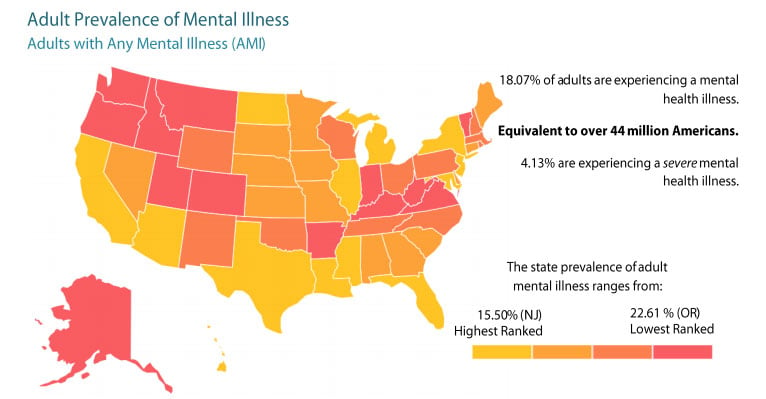

America has a mental health crisis.

According to the National Council for Behavioral Health, one in four Americans have had to choose between getting mental health treatment and paying for daily necessities. And more than half have tried to “grin and bear it” instead of seeing a doctor.

Just 26% of students suffering from mental health issues said they received real assistance.

This crisis extends into the world of science and scientific research.

Surveys have shown that graduate students were more than six times likelier to show moderate to severe anxiety or depression on average.

The pressures of the scientific world are numerous, and can sometimes be overwhelming.

These can begin before even entering a PhD program—prospective scientists are told over and over again that it’s hard to get in, that many don’t finish, that it’s difficult to get grants and nearly impossible to become a professor. Scientists face intense demands: to work long hours, to publish frequently and in high-profile journals, and to win grants, all the while being expected to bear rejection after rejection.

While the pandemic has arguably worsened the mental health crisis, both in science and around the world, greater awareness has led to more strategies for coping as well as more structural solutions.

In this series, we’ll examine the greatest mental health issues facing scientists today and how we might overcome them.

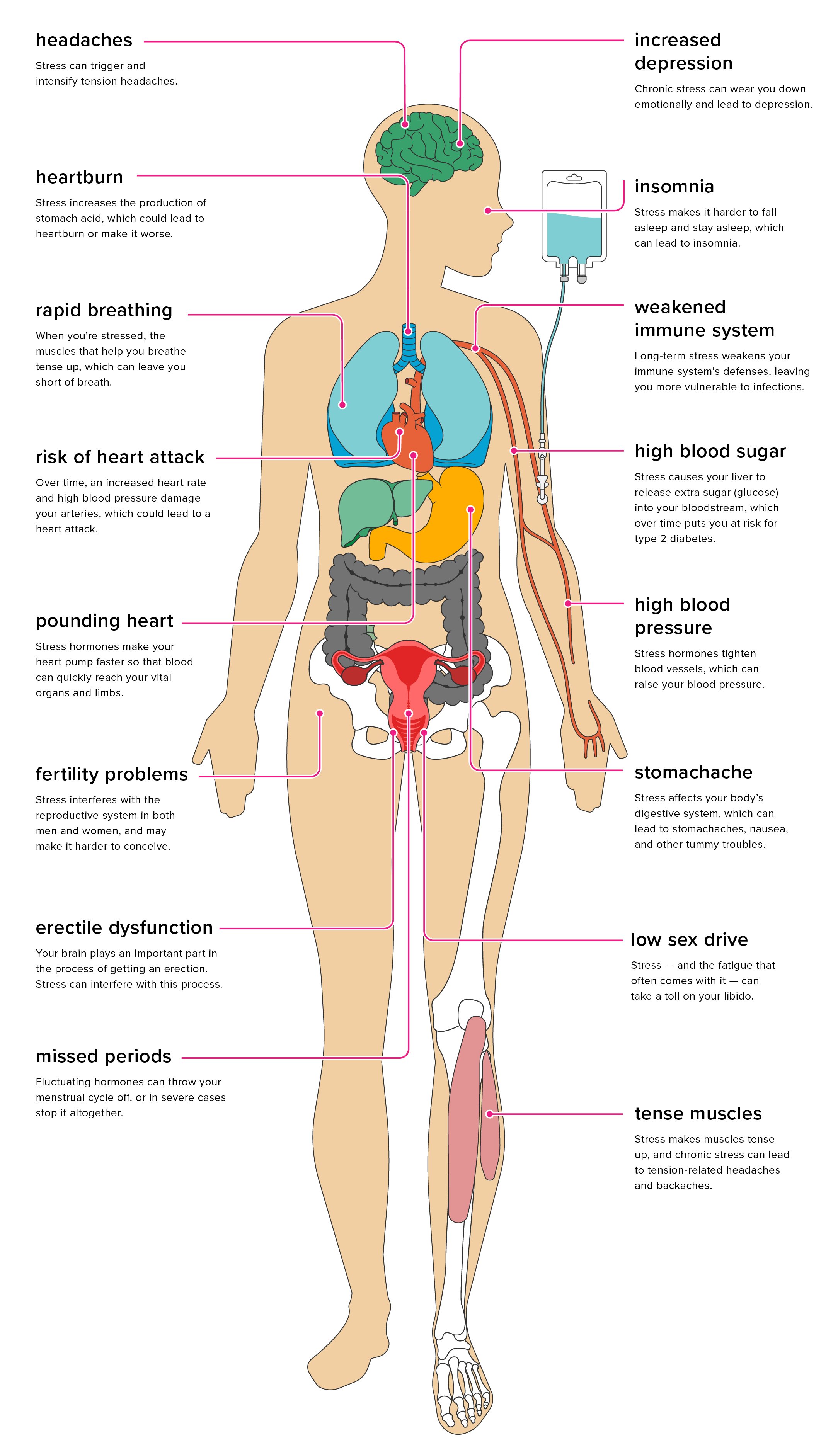

Stress and burnout

Stress and burnout are rampant in academia, where intense pressures, heavy workloads, and poor work-life balance contribute to deteriorating mental health. For graduate students, having to juggle coursework and research, while suffering anxiety over future job prospects, can be an especially swift route to experiencing burnout.

One survey found that 50% of early career researchers work more than 50 hours a week—significantly more than as specified in their contracts. And with high workload comes high stress.

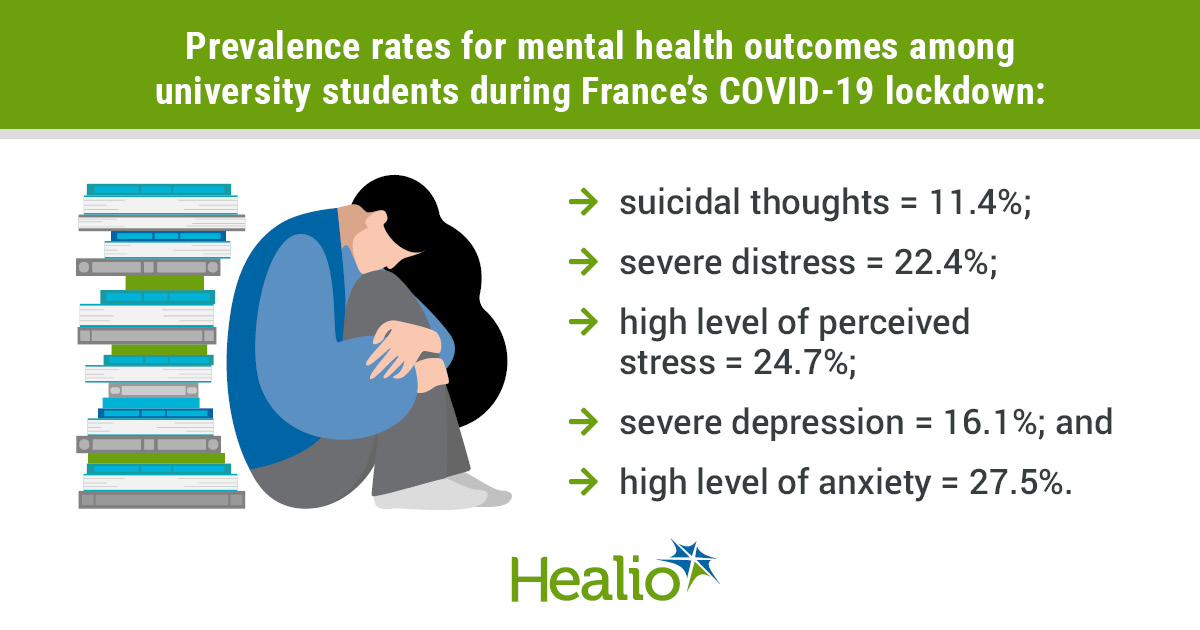

These issues have only compounded with the pandemic and its logistical challenges, lay-offs, hiring freezes, and funding crunches. In a 2020 poll, the number of stressed US faculty members more than doubled compared to 2019. More than half of people surveyed said they were seriously considering changing their career or retiring early. 75% of women, burdened by childcare obligations and deteriorating work-life balance while working from home, reported feeling stressed. Other marginalized groups such as international students and LGBT+ researchers experienced a disproportionate increase in burnout. These numbers proved to be similar in Europe.

Per the Harvard Business Review, stress and burnout can also have an adverse impact on decision making. You think you don’t have time for actions that would help you in the long run, like practicing self-care or taking a vacation. You don’t utilize your unconscious mind, which can be an extremely valuable problem-solving tool when given time to wander freely during walks, exercise, or errands. You tend to withdraw from emotional support lifelines and become more rigid, defaulting to our dominant methods of problem solving rather than staying flexible and creative. All of these issues can compound for scientists, who are expected to work long hours and solve extremely challenging problems—while research suggests that our brains only have around four hours a day of intellectual work in them.

Scientists are more stressed than ever before. So how can you manage stress and burnout, especially during the pandemic?

Tips and tricks

- Read a book, go for a run, cook—anything that successfully detaches you from the source of the stress.

- Don’t be alone. Regularly talk about issues with peers, colleagues, and families. Don’t suffer from stress alone.

- Adjust expectations. Schedule more time than necessary to meet work and family obligations. Expect yourself to be tired—that way you can separate exhaustion and burnout from failure.

- Have a long-term view. Stress and burnout create both short-term and long-term problems for overall productivity and research success. It’s better to take a break now than to suffer later.

- Cover the basics. Healthy eating, adequate sleep, and periodic exercise are proven to be linked to better mental health and a stronger immune system. Ensure that your schedule allows for these bare minimum basics—and even better if it allows for some fun and socializing, too.

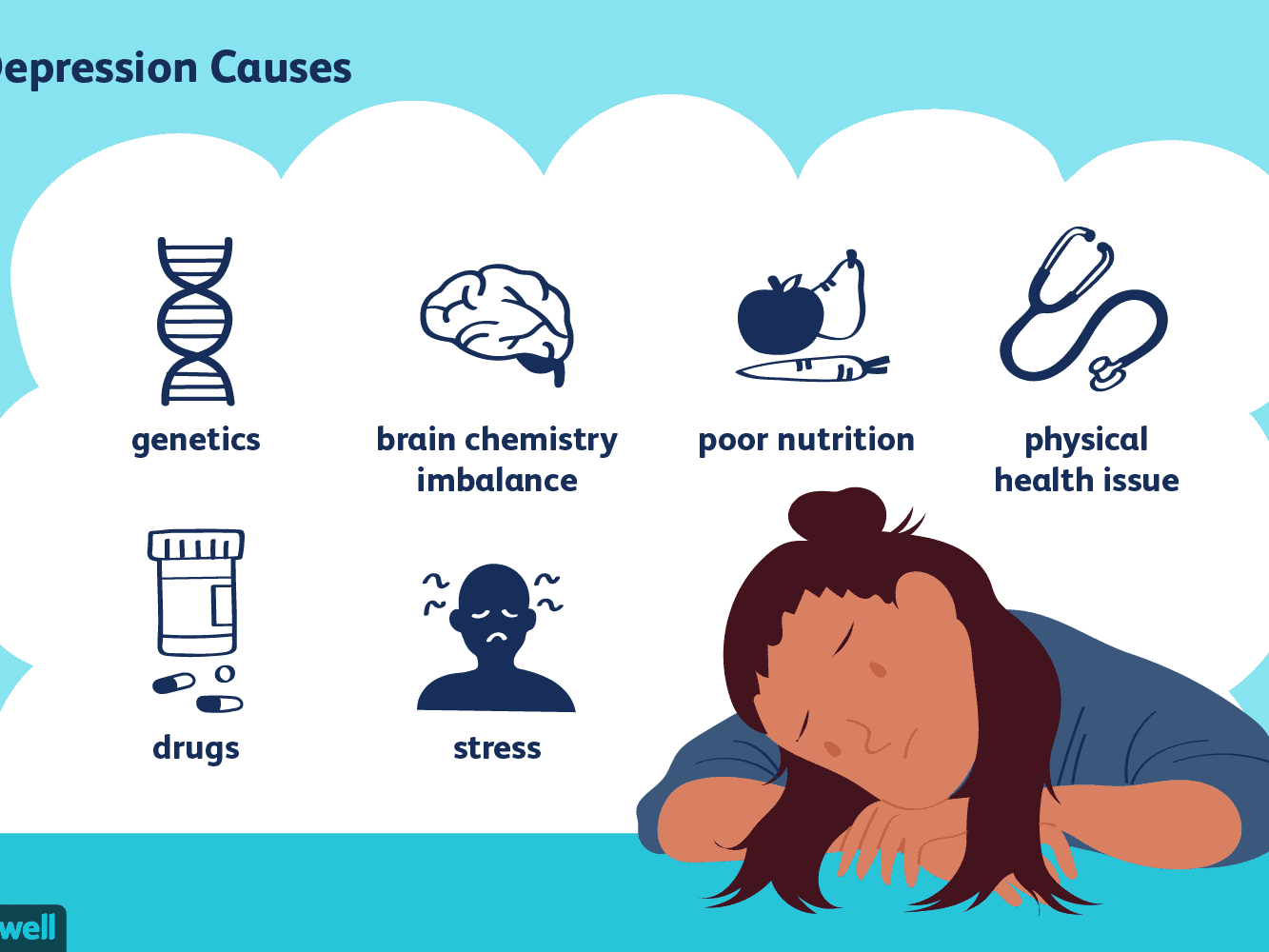

Depression

Depression is a serious problem among researchers. In particular, depression has been widely tracked and observed in graduate students. Researchers at Ghent University in Flanders showed that one-third of PhD students were at risk of developing common mental-health disorders, primarily depression or anxiety—a risk more than twice as high as other highly-educated groups in Flanders. The study went viral, ringing true with many PhD students around the globe.

Even worse, many students have failed to find real care at their institutions—according to one survey, just 26% of students suffering from mental health issues said they received real assistance. Experts say that most institutions simply do not have enough capacity of counselors and resources to meet demand. Universities investing more into mental health is one solution, but solving the underlying problems of overwork and immense expectations is likely to be far more effective.

How can you deal with depression as an individual in science? A lot of it revolves around self-recognition and reflection.

Tips and tricks

- Recognize your pattern—and seek help. If you find yourself struggling to get out of bed in the morning every day, recognize that a doctor might be able to help you. Many scientists who have gone through serious mental health issues acknowledge that their lives only changed for the better once they were properly diagnosed and medicated.

- Know your limits. Applying to post-docs and professorships can be a crushing, brutal experience. If it’s ruining your ability to function, it might not be worth it. See if you can stay with your current lab for another year to get back on your feet. Sometimes, an objective might be out of reach or too damaging for your current circumstances—and recognizing that is a good thing.

- Remember that you’re not alone. You can only succeed when surrounded by a healthy support network of people. If your institution, mentors, and colleagues are failing to support you or recognize you as a human being, it may be the wrong organization for you. It’s impossible for anyone to succeed when in the woods like that.

Imposter Syndrome

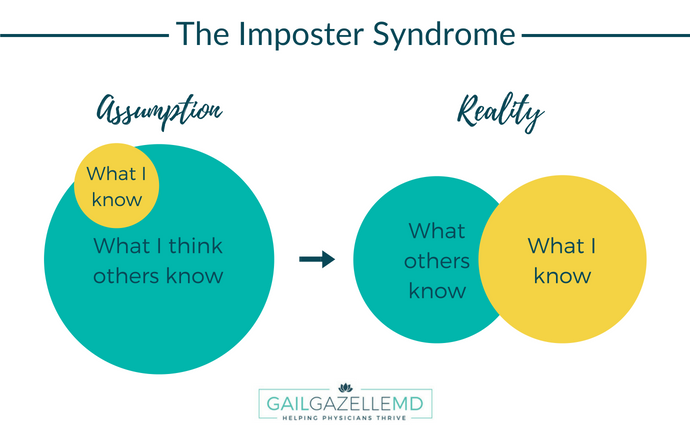

Imposter syndrome is that self-doubt and sense of inadequacy that persists no matter what you’ve achieved or accomplished. While it’s a common phenomenon in many professions and industries, it has a significant impact on scientists. Science is a field that demands a series of accomplishments—high scores on exams, successful grant proposals, paper acceptances. And while failure is a normal part of the process, the feeling of being surrounded by others more successful than oneself can become a serious mental health burden.

Researchers at top institutions in particular can experience imposter syndrome after moving from environments where they were top performers to one where they are merely average. Self-doubt can be a career-killer when it ends up discouraging researchers from pursuing opportunities. “I saw many students who were shooting themselves in the foot,” Josh Drew, an evolutionary ecologist at Columbia told Nature. “They weren’t applying for grants and awards that they would be competitive for.” Many notable scientists have admitted to struggling with imposter syndrome—and have further experienced the negative impacts that this kind of paralysis can have on careers.

Tips and tricks

- Language matters. Don’t minimize your accomplishments by saying ‘just’ or ‘only’ when describing your own work, and don’t apologize for every mistake.

- Build communities. Members of underrepresented groups should seek out communities where they can see themselves represented, even if only online. Seeing examples of people like yourself having success in science can be the best kind of encouragement.

- Embrace failure. Failure is just a part of the scientific process—and the process of having a career in science. Talking about and admitting failure can create a more positive environment for all. This starts at the top, with institutional leaders and lab directors, and should extend throughout the scientific community.

Technology

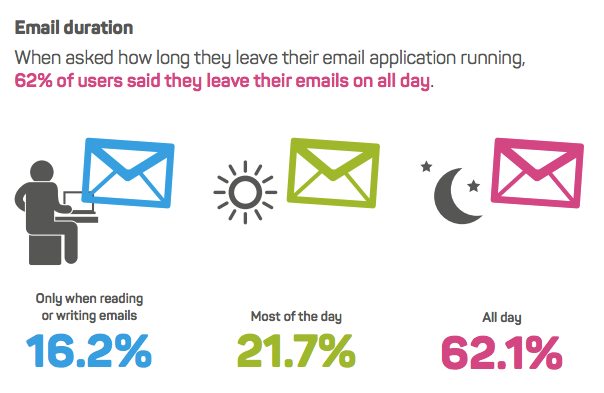

While we’re not shy about mentioning the benefits that technology can bring to scientists and researchers, it does pose its own set of mental health challenges. These can be subtle effects, such as how digital texts encourage a shallower engagement with the text as compared to print. But they can also be more pervasive, such as the link between the burgeoning digital environment and shortening attention spans, as well as the link between digital communications and stress.

Research has shown that some of these effects tend to be temporary. Leaving your phone in another room can simply make the attention span problem go away. But other stresses are more persistent. The ‘phantom pocket’ phenomenon, where people perceive non-existent notifications from smartphones, is rooted in the stress that digital communication causes.

By far the most obvious harmful effect of technology, however, is on sleep. There are significant differences in sleep between people reading on paper versus on screens before bed, and the research shows that sleep is disrupted by mobile phone use.

As the environment of science is increasingly digitized, it has become clear that ideally, scientists need to find a balance. Scientists should use the latest technology to make their lives and jobs easier, while frequently detaching from technology in order to preserve their mental health.

While the verdict is not yet out on just how drastically technology can affect mental health, getting wired to work via portable smart phones is an obvious source of stress. Removing these devices from your environment when possible is the most surefire way to escape.

Root causes

Stress, burnout, depression, imposter syndrome, and more are all major mental health challenges pervasive in science, research, and academia. We previously shared tips for individuals on how to deal with these problems, but what about a deeper institutional look at how to address their root causes?

One root cause of stress in science is the scarcity of professional advances in the research world. Most researchers follow temporary contracts, gradually getting expelled as they fail to reach higher echelons (i.e. tenure). Research centers can incorporate information sessions on alternative paths in research outside academia. If a career as a researcher at a university becomes seen as just one option among any, pressures will decrease significantly.

Another root cause is the higher working hours expected of researchers (about 38% of young researchers work more than 60 hours). A body of research suggests that the number of hours spent on research is not directly proportional to the number of publications and their relevance. “Working 50-60 hours a week is a mistake that weighs down on originality and creativity,” says Fernando Maestre at the University of Alicante. “We must banish the myth of the researcher who is obsessed day and night with his work.”

The concept of ‘excellence’ has become a target for experts attempting to change the intensely stressful culture of science. The hyper-competitiveness of scientific careers and publishing not only harms laboratory environments but also the quality of science, which increasingly lacks reproducibility.

One proposal for a way to shift this is to change the narrative of scientific excellence towards one based on ‘soundness and capacity,’ and to enhance the concept of ‘normal science,’ where quality is based on procedures and not necessarily on results. These ideas come from a proposal at King’s College London, which further proposes to create a funding system which almost all groups receive base money, reducing pressure to publish.

Scientific research is an intense and challenging profession that has many potential impacts on an individual’s mental health. But it is also an intensely rewarding one. Making sure that you know how to navigate stress, burnout, depression, imposter syndrome, and technology will be sure to enhance and elongate a successful career in research.

Hopefully in the future we will see a world of scientific research that is less hyper-competitive and allows for greater work-life balance. These big picture changes—from having a broader view of success to less all-consuming schedules—will have just as great of an impact, if not greater, than looking after one’s individual mental health.