In response to the rapidly spreading and fear-inducing coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China, scientists from academic institutions in New Delhi published an article that claimed to find similarities between coronavirus and HIV.

The paper, published on bioRxiv, a popular biology preprint server, had rushed the likely coincidental findings. Swiftly deemed false by scientists across social media, the paper was soon retracted.

Some hand-wringing scientists decried the lack of peer-review on preprint servers like bioRxiv. But if the findings had really been true, they would have been dire enough to demand an immediate platform. With a traditional peer-review publishing process, the findings wouldn’t have been published until months down the line—at the absolute earliest.

That's exactly why preprints make sense.

They don’t claim to be rigorous scientific results or discoveries. They’re drafts, submissions of ideas that deserve consideration. They’re sent out into the world to get helpful feedback as well as to ensure that fresh and exciting ideas get heard as soon as they’re conceived.

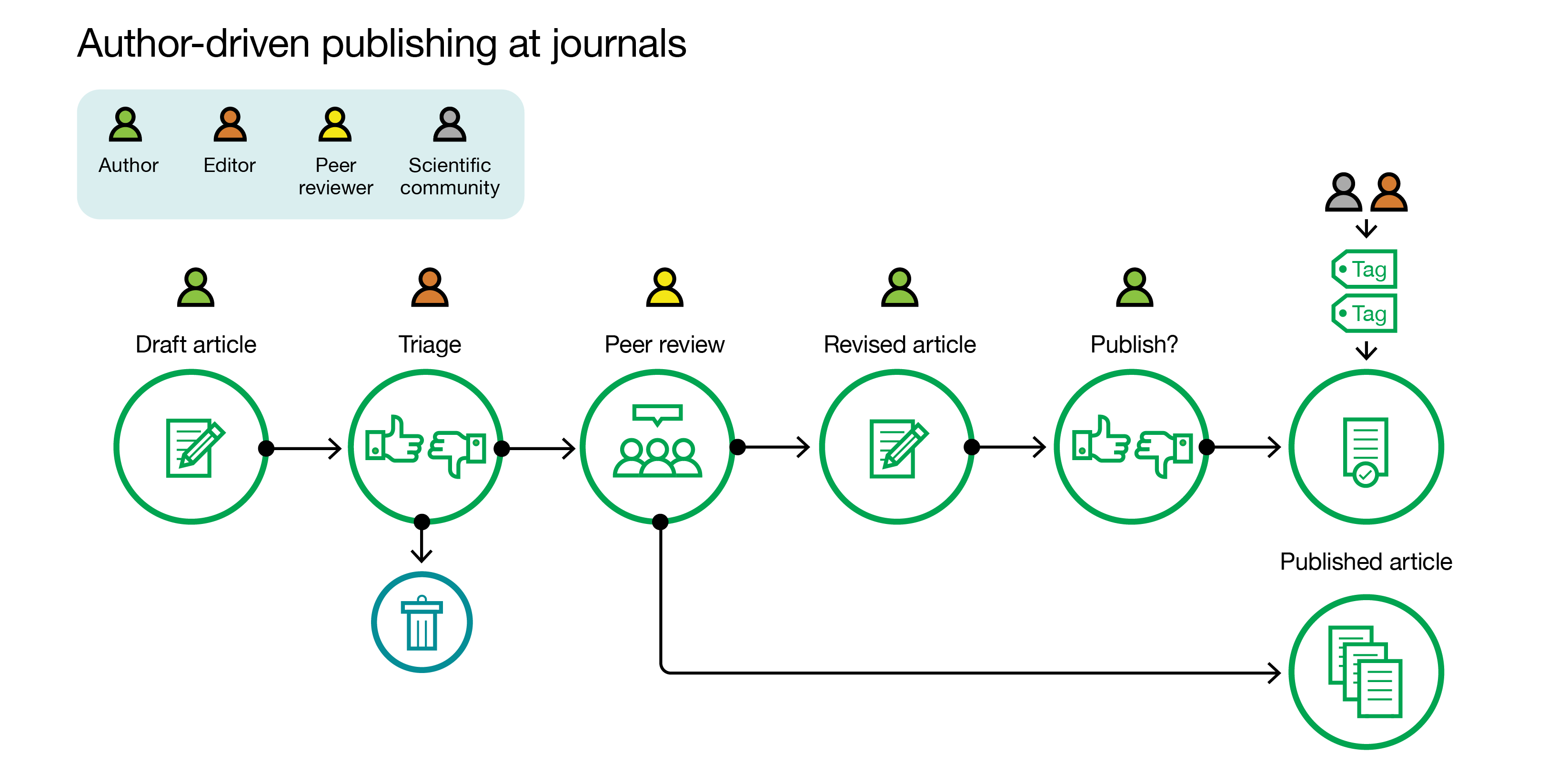

While more and more institutions and scientists attempt to break free from traditional publishing in favor of open access research, widespread criticism of the traditional peer review process has circulated among the scientific community for years. At the same time, social media has transformed scientific discourse, with serious and impactful discussions happening on platforms such as Twitter on a regular basis.

The traditional peer review process and system of academic publishing does have real benefits. They offer rigorous review, longstanding reputation, strong hosting technology, and well-funded publishing, marketing, and distribution processes. Those seeking to move away from the status quo face an uphill climb.

Preprints nevertheless can fulfill the essential role of providing early insight into new research developments—and begin to offer solutions to some of the most pressing challenges facing science in the 21st century.

Main challenges in scientific publishing

The peer-review and scientific publishing process currently face a number of pressing issues. The top five are as follows:

- The current process is widely recognized as too time-consuming.

On average, the entire peer review process takes 17 weeks. To put this in coronavirus terms, if the false paper published on bioRxiv had gone through a traditional process, indications that coronavirus had similarities with HIV would not have been seen by the scientific community until the week of May 24th—nearly six months after China announced the discovery of a new virus.

Even though it’s possible to review a paper in less than a day, most papers remain unexamined on an editor’s desk for weeks. A 2017 study found that one-third of papers require more than two weeks for an immediate desk rejection. Complaints that the process is too slow are as old as the process itself, and research has indicated that it’s getting even slower than it used to be as the number of rounds of review has increased over time along with the overall number of studies.

- Reviews are anonymous and vary in quality.

Researchers review papers without any compensation, which not only is a huge disincentive to get the review done quickly and efficiently but also leads to enormous variations in the quality of peer reviews. Some reviews are deep and insightful; others are shallow and lazy. With the entire peer-review process cloaked in secrecy and done out of good-will (since reviewers are not identified or compensated), laziness and bias can get in the way of effective peer reviews.

- Journal impact factor is too big a factor.

Much (and arguably too much) attention in the field is paid to the journals regarded as the journals with the higher ‘Impact Factor’ or JIF, like Nature and the New England Journal of Medicine. This isn’t usually a bad thing, but even the best journals have rejected big discoveries, including Nobel Prize winning studies. Since JIF essentially rewards journals for publishing the highest possible ratio of highly-cited papers to total number of citable items, some peer-reviewed journals are incentivized to be overly selective.

- Peer review feedback can’t be seen by most of the scientific community.

Papers are only viewable in final form, without any of the feedback or discourse that developed the ultimate finding of the study. This deprives readers of the chance to understand the research process that went into the findings—which is crucial information for advancing further discoveries in the field, as well as key materials for educators training the next generation of scientists.

- Only peer-reviewed articles (and especially ones in top publications) count towards career evaluation.

Publishing in peer-reviewed journals is the literal key to career success for scientific researchers. A single article in a top-tier publication can make a career. But considering the many other drawbacks with the peer-review and publishing process, the fact that institutions rely on this flawed system to hire and promote scientists only multiplies every prior issue mentioned, and lends them career-altering stakes.

Put simply, preprints provide another avenue for research to be published, evaluated, and shared—mitigating several of these challenges. So what are preprints, and how do they help?

What's a preprint?

A preprint is a version of a scientific paper published in an accessible platform that precedes formal review and publication in a mainstream peer-reviewed journal. It’s an earlier draft that (like any early draft of a paper) may have errors, but is nonetheless worth sharing with the scientific community because the author doesn’t want to wait weeks to receive simple feedback from their peers, or because the author believes they have timely findings that should be seen, or because they want to set precedent on a research topic or any other number of reasons.

Scientists usually publish preprints before or in parallel with the peer-review process, as preprints are considered to establish precedent. That means that scientists cite preprints that they are aware of and have considered during their research.

To avoid confusion, all preprint platforms indicate on the website that papers have not undergone peer review. Preprint platforms, of course, do provide some level of screening for basic scientific content, author background, and compliance with ethical standards, but it can vary from server to server and certainly doesn’t compare to the rigor of peer review.

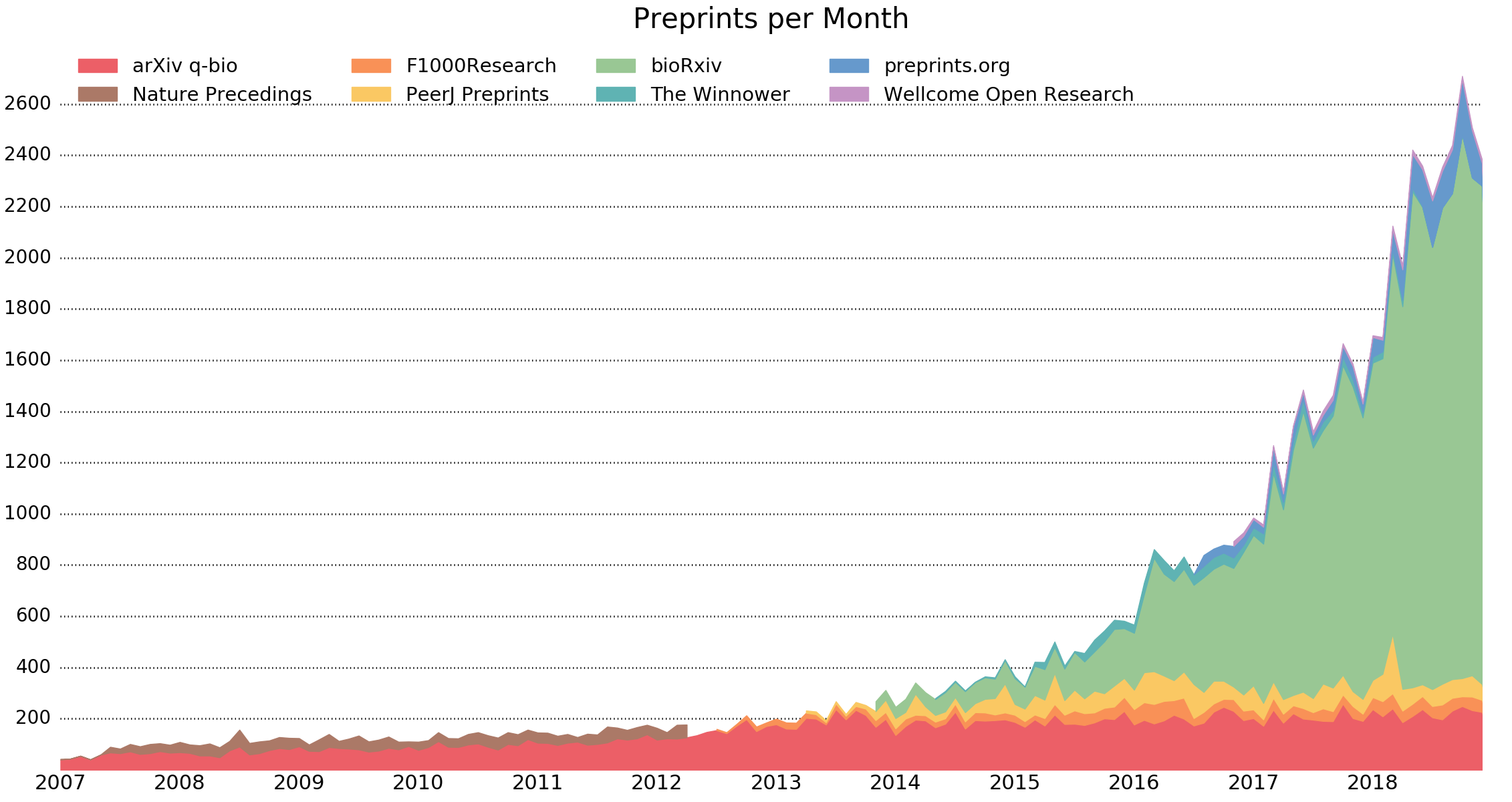

Preprints have different levels of prominence in different fields. Preprints have been popular and even commonplace in certain fields like physics and economics as early as the 1990s, while they have only recently spread to other disciplines like medicine and ecology.

With the preprints world currently earning more attention, the landscape is fragmented among many different platforms and technical solutions for hosting and disseminating research. The online interfaces for viewing preprints can be completely different from platform to platform, as some preprint platforms go so far as to work like social media sites, with the number of views and downloads listed publicly along with commenting functionality.

Why use preprints?

Preprints solve many of the above problems with contemporary research. Knowledge Exchange released a report on the transformative role of preprints in fall 2019, showing that the scientific community saw fast dissemination of research and increased opportunities for feedback as the two main benefits.

The main benefits to preprint publishing include:

- Instant dissemination and opportunity for feedback

- Preprints can be added to CVs to help early-career scientists with getting hired

- With over 60 platforms available today, there is a server for every niche and field

- Preprints are openly accessible, increasing chances for widespread feedback and dissemination, especially through social media

- Publicly available preprints also make it easier for scientists to find valuable information and ongoing discussions in their field

- Preprints provide an additional factor for research evaluation in hiring and funding

Knowledge Exchange reported that many of the scientific communities concerns with preprints are only perceived barriers. Most peer-reviewed journals now explicitly accept articles that have been previously shared as preprints.

Some argue that while preprints are good for the research community itself, they could lead to the media increasingly reporting on false results. That’s because preprints would disrupt the status quo of close communication between researchers and science journalists who report exclusively on their peer-reviewed studies. However, Knowledge Exchange argues that the expectation for scientists and media to behave ethically will help reduce any related negative impacts.

How preprints will evolve

The Knowledge Exchange notes that preprints may be riding a hype wave this year, so in the short term the use of preprints may actually shrink. But given the overall growth of preprints—more than half of the existing preprint servers were created in the last five years alone—as well as the relevant discussion around them, at the very least they will put pressure on traditional journals to change as young researchers increasingly turn to preprints in the hopes of boosting their careers.

Given how widely dispersed preprints are among different parties and servers, no one group looks poised to take the lead or set a clear precedent. A major question is whether researchers or publishers will take responsibility for preprints and who will fund their servers.

One trend is clear: scientists are increasingly thinking and reacting fast. With ample evidence that being active on Twitter can further scientific careers and literally boost the number of citations that a paper receives, scientists are more likely than ever to share their work on social media, and comment, like, and re-share the work of others. In an explosive and evolving media and social media landscape, traditional academic publishing, while founded on rigorous methods, has become frustrating and simply too slow for many.

Will the hype wave die out, or is this the beginning of preprints becoming an established part of the scientific process? Only time will tell. Regardless, most scientists will find it worth their time to explore whether preprints can help them obtain feedback, find important and breaking research, and even boost their careers.

Exhaustive list of preprint servers

|

AgriXiv |

Agriculture |

|

|

BioHackrXiv |

BioHackathons |

|

|

ChemRxiv |

Chemistry |

|

|

Cogprints |

Cognitive Science |

|

|

Electronic Colloqium on Computational Complexity |

Computer Science |

|

|

Cryptology ePrint Archive |

Cryptology |

|

|

EarthArXiv |

Earth Sciences |

|

|

ESSOAr |

Earth Sciences |

|

|

EcoEvoRxiv |

Ecology |

|

|

RePEc |

Economics |

|

|

MRPC |

Economics |

|

|

ECONSTOR |

Economics |

|

|

NBER Working Papers |

Economics |

|

|

EdArXiv |

Education |

|

|

ECSarXiv |

Electrochemistry |

|

|

engrXiv |

Engineering |

|

|

SSRN |

General |

|

|

HaL |

General |

|

|

ResearchGate |

General |

|

|

viXra |

General |

|

|

figshare |

General |

|

|

Authorea |

General |

|

|

Zenodo |

General |

|

|

Preprints.org |

General |

|

|

OSF Preprints |

General |

|

|

Gates Open Research |

General |

|

|

WikiJournalPreprints |

General |

|

|

AfricArxiv |

General - Africa |

|

|

Arabixiv |

General - Arabic |

|

|

ChinaXiv |

General - China |

|

|

FrenXiv |

General - French |

|

|

IndiaRxiv |

General - India |

|

|

INA-Rxiv |

General - Indonesia |

|

|

CORE repository |

Humanities |

|

|

Advance |

Humanities |

|

|

LawArXiv |

Law |

|

|

E-LIS |

Library & Information Science |

|

|

LIS Scholarship Archive |

Library & Information Science |

|

|

bioRxiv |

Life Sciences |

|

|

F1000Research |

Life Sciences |

|

|

PeerJ Preprints |

Life Sciences |

|

|

LingBuzz |

Linguistics |

|

|

MarXiv |

Marine science |

|

|

Mathematical Physics Preprint Archive |

Mathematics |

|

|

MediArXiv |

Media & Communication Studies |

|

|

JMIR Preprints |

Medicine |

|

|

Wellcome Open Research |

Medicine |

|

|

MedRxiv |

Medicine |

|

|

BodoArXiv |

Medieval Studies |

|

|

MindRxiv |

Mind and contemplative practices |

|

|

NutriXiv |

Nutritional Science |

|

|

PaleorXiv |

Paleontology |

|

|

CERN Document Server |

Particle Physics |

|

|

PhilArchive |

Philosophy |

|

|

PhilSci-Archive |

Philosophy of Science |

|

|

APSA Preprints |

Political Science |

|

|

PsyArXiv |

Psychology |

|

|

arXiv |

Sciences |

|

|

SSOAR |

Social Science |

|

|

SocArXiv |

Social Science |

|

|

MetaArXiv |

Social Science |

|

|

SportRxiv |

Sport science |

|

|

Therapoid |

Therapeutics |

|

|

Thesis Commons |

Theses and dissertations |

|

|

FocUS Archive |

Ultrasound |